|

Other issues: |

English |

Finnish |

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

2009 - No 1 (Plan 2. ed.) | |

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

|

2008 - No 1 (Suojelusuunnitelma 1. laitos) |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

2009 - No 2 (Esite pdf) |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

- Translator's Note Lauri Kahanpää

Lauri Kahanpää

Dear Friend.

Three Finnish issues of the Bulletin have already appeared in 2009. Number 1 contains on 44 English pages our detailed plan of how to reintroduce the Lesser White-fronted Goose to Finland. The Finnish issues are our Brochure and an ordinary Bulletin. This issue - number 4 - contains most of the material of the Finnish Bulletin 3/09 in English.

Antti Haapanen

Credit was given to the monitoring done by the LWfG group of WWF Finland and NOF/BirdLife Norway, but we did not believe in the prospects of reaching positive results by conventional methods. Instead, we proposed captive breeding of the species in Finland and reintroduction with the Swedish method. The core feature of this method is that the reintroduced birds migrate to the south-west instead of the south-east like the remnant Norwegian LWfG population is doing.

31.5.2004 the Ministry gave an answer to the letter writers. The idea of breeding and releasing was not accepted. As a goal the Ministry set support to the Norwegian birds. Only the work organized by the WWF group was considered worth while continuing. Also, the Ministry proposed a common meeting to specify the goals of LWfG conservation for the next ten years. Interestingly, the Ministry sent a copy of the letters to WWF but not to the Friends of the LWfG.

2.4.2005, continuing the international conference, a domestic meeting was held. In this meeting the overall situation was discussed. Among other subjects the immediate need to secure continued breeding and breeding skills were taken up. This was most relevant for the Friends of the Lesser White-fronted Goose. The meeting made no decisions. The minutes, written more than a month later, were sent to, (not checked by) all participants and to the Ministry of the Environment, whose representative was present also. The domestic meeting did not lead to any improvement. In spite of several applications, no support for LWfG reintroduction or keeping up breeding skills was given.

The Attorney General made his decision on 29.5.2008. The following four actions by the Ministry were critisized:

The following three actions by the Ministry were accepted by the Attorney General:

The second permit application was delayed in the Uusimaa Environmental Center which had consulted the Ministry of the Environment. The ministry did not give an answer in due time. It took two years until, after the above mentioned criticism from the side of Attorney General, a quick negative decision was made. The Society complained to the local administrative court in Helsinki. Since no decision was made during 2008, we drew back the original, now obsolete application.

The only legally binding decision is the positive decison by Turku local administrative court. The permissions should have been granted.

20.4.2009 the Friends of the Lesser White-fronted Goose sent another letter to the Ministry of the Environment, this time stating that the Ministry's 2.3.2009 decision on "Action Plan for Protection of the Lesser White-fronted Goose" was insufficiently prepared and its scientific points were questionable, to some part right out false. Therefore, the Society proposes the nomination of a working group for re-preparation of a new plan. This group should encompass the relevant parties and set the clear aim to restore the favorable conservation status of the Lesser White-fronted Goose in Finland. This means reintroduction of the species as a breeding bird.

118.8.2009, the Regional Environmental Centre of Lapland granted some rangers of the Natural Heritage Service the permit to "eliminate" the Lesser White-fronted goslings and their foster parents released by us in Finnish Lapland. And the local police were asked to survey whether we have released an alien/exotic species (B. leucopsis!) in Finnish Lapland! We hope for a quick decision of the regional prosecutor on whether this case is taken into a court or not, to be able to continue without delay. A similar case was already in the court 05.09.2005 and was decided in our favour.

So the story will continue.

Erkki Kellomäki and Lauri Kahanpää

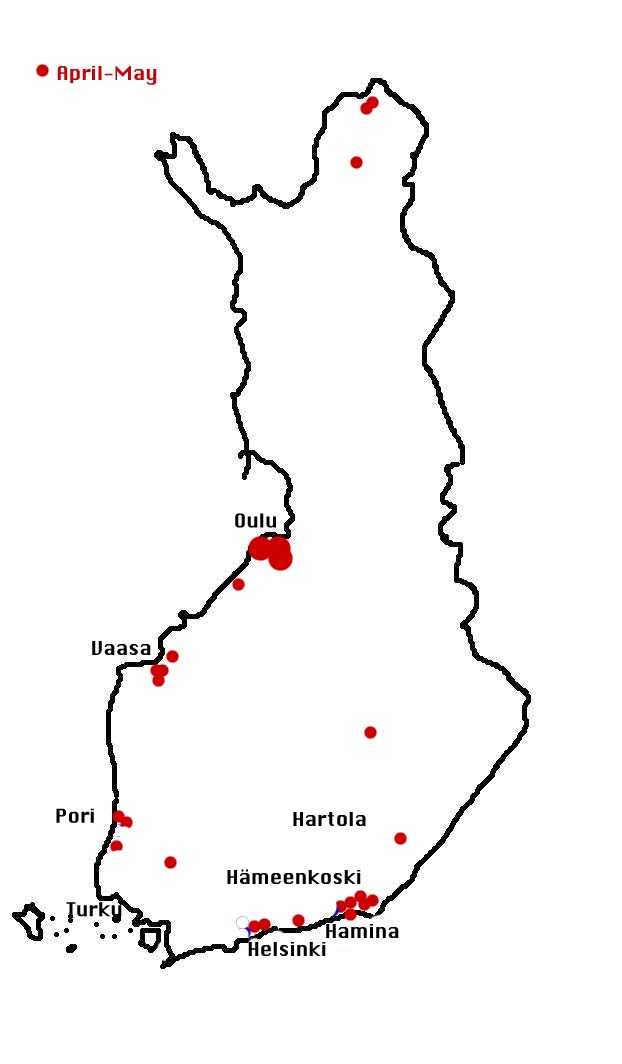

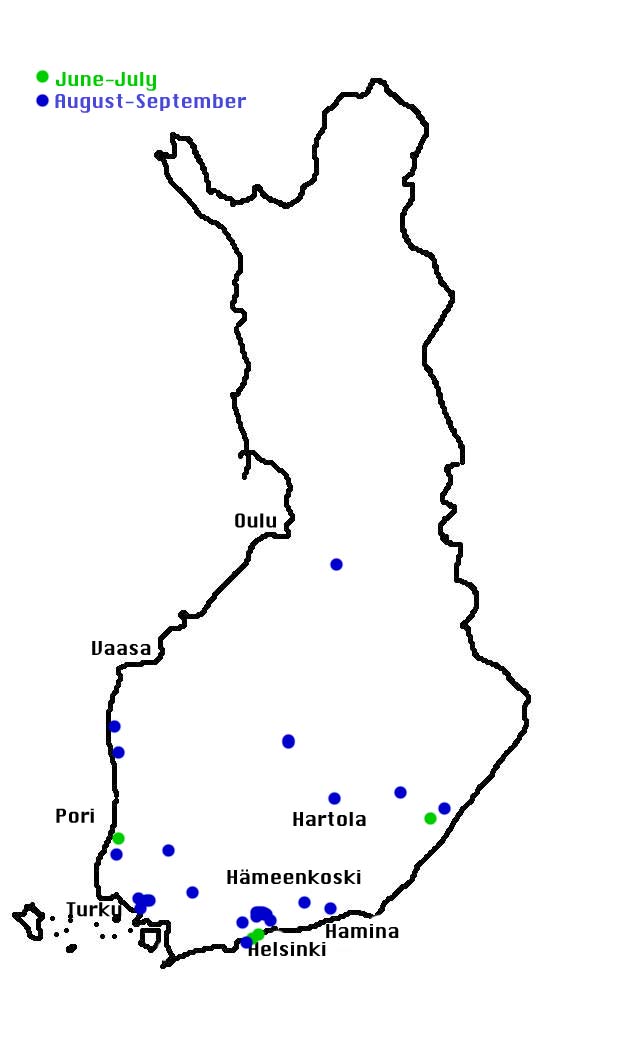

Distribution of Finnish LWfG observations in spring and autumn 2000-2009

A glimpse at the map shows that the autumn migration pattern differs sharply from the spring pattern. The main difference is the absence of the flocks at the Gulf of Bothnia, in fact the absence of any flocks and of any observations between Oulu and Vaasa. Observations of single birds, usually in company of other geese, scattered around the southern half of the country, in particular the south coast, tell the story of the same few Russian birds that came in spring from the west now flying back. A special phenomenon are the "urbanised" individuals that have stayed in the Helsinki metropol area for weeks. Parks and golf courses provide ideal food and safety for other grazing goose species, so why not for the LWfG. The phenomenon is well documented in Sweden where the largest autumn flocks are counted grazing in the city park of Hudiksvall.

There are some documented summer observations of LWfG in Finland. Most of them concern single idividuals which stayed all summer stationary on some lakes in southern Finland demonstrating that the species can well survive with "southern" food. On the other hand, none were breeding or breeding or returnined next year. The newest observation, not marked on the map, is from Lapland. In June 2009, a flock of no less than 5 LWfG was seen relatively close to one of our releasing sites. These birds may well be evidence for the first breeding of the LWfG in Finland since 1998.

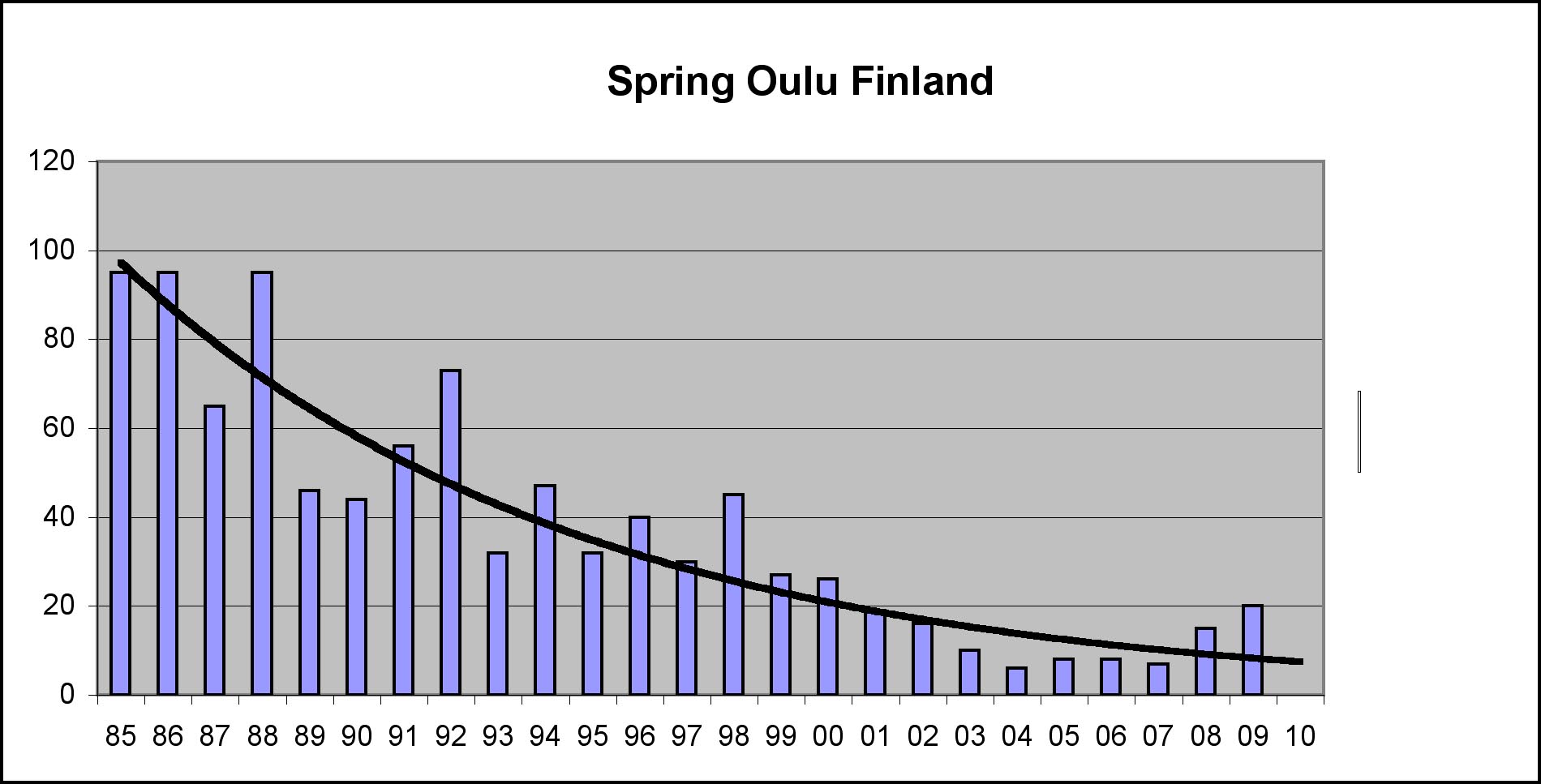

Lauri Kahanpää (data LWfG Life Project)

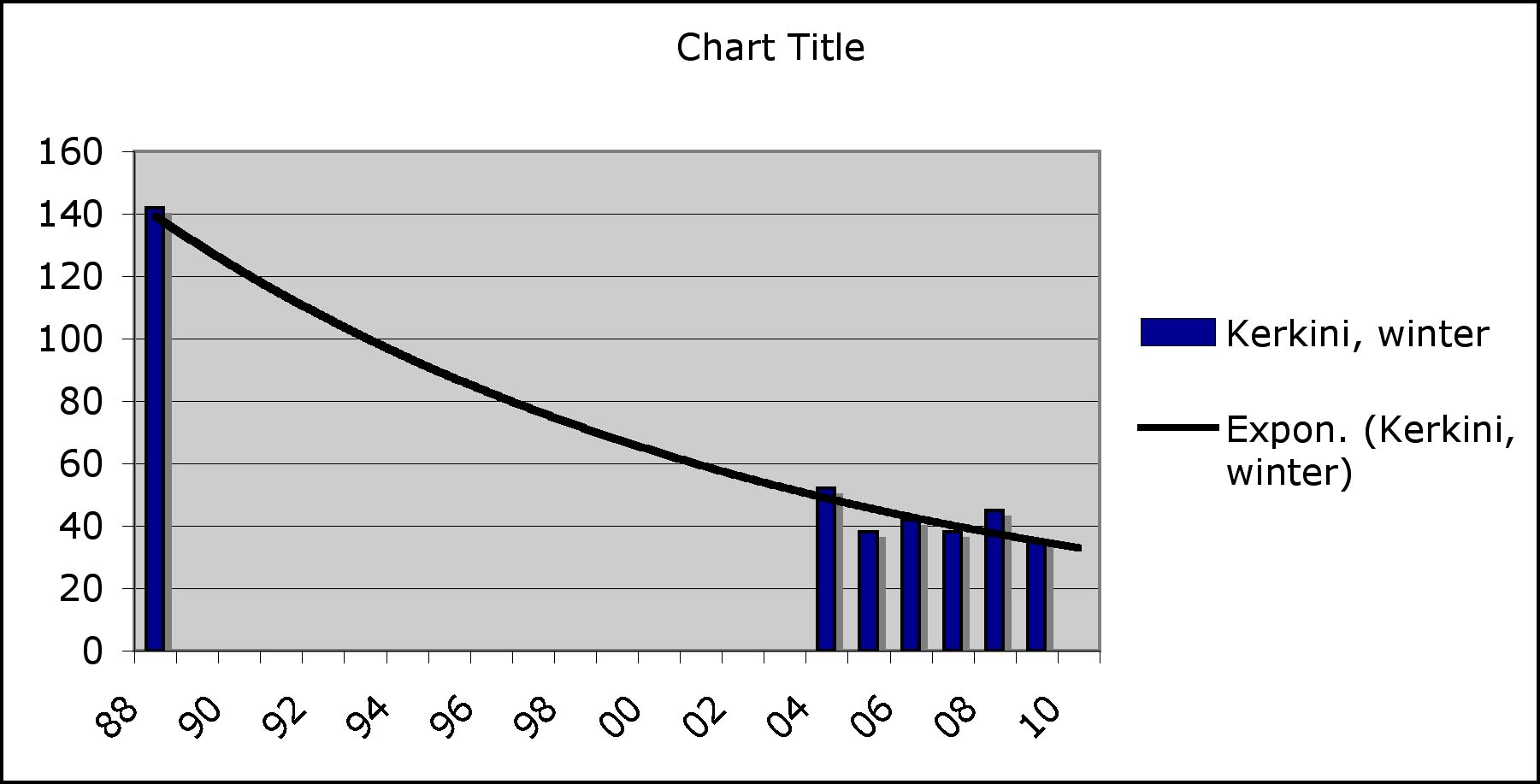

In December 2008, there were at best 45 Lesser White-fronted Geese in Greece, among them four young birds who later disappeared. In mid winter they stayed on Lake Kerkini and none were seen in the Evros river delta. At the same time, there was another flock in Hungary and Austria: 25 LWfG of which five were young. There is strong evidence for these birds to have flewn in from Russia. They were seen at a slightly different site, and some of them carried individual marks not seen before. The same can be said of winter observations at various places in Bulgaria, Poland, and Germany.

In March, the LWfG left Greece for Hungary, and the flock arrived at the usual Hortobágy resting area. Two (4%) were lost on the flight.

Spring observations at Hortobágy, Hungary

In April, migration was continued towards Norway. In Estonia, 30 LWfG were seen, 23 of them in the Tahu area in Noarootsi and some more on the traditional Haeska meadows.

In May, the LWfG were counted in Finland. A flock of 21 individuals, 3 of them young, rested on the usual fields in Siikajoki near Oulu, and some more were seen on the most traditional site in Hailuoto which had been empty for years. Like in Estonia, the Finnish total adds up to 30. Evidently, most Norwegian LWfG made a stop in Finland this year. Since something similar was observed last year, this may be a permanent change in their migration pattern.

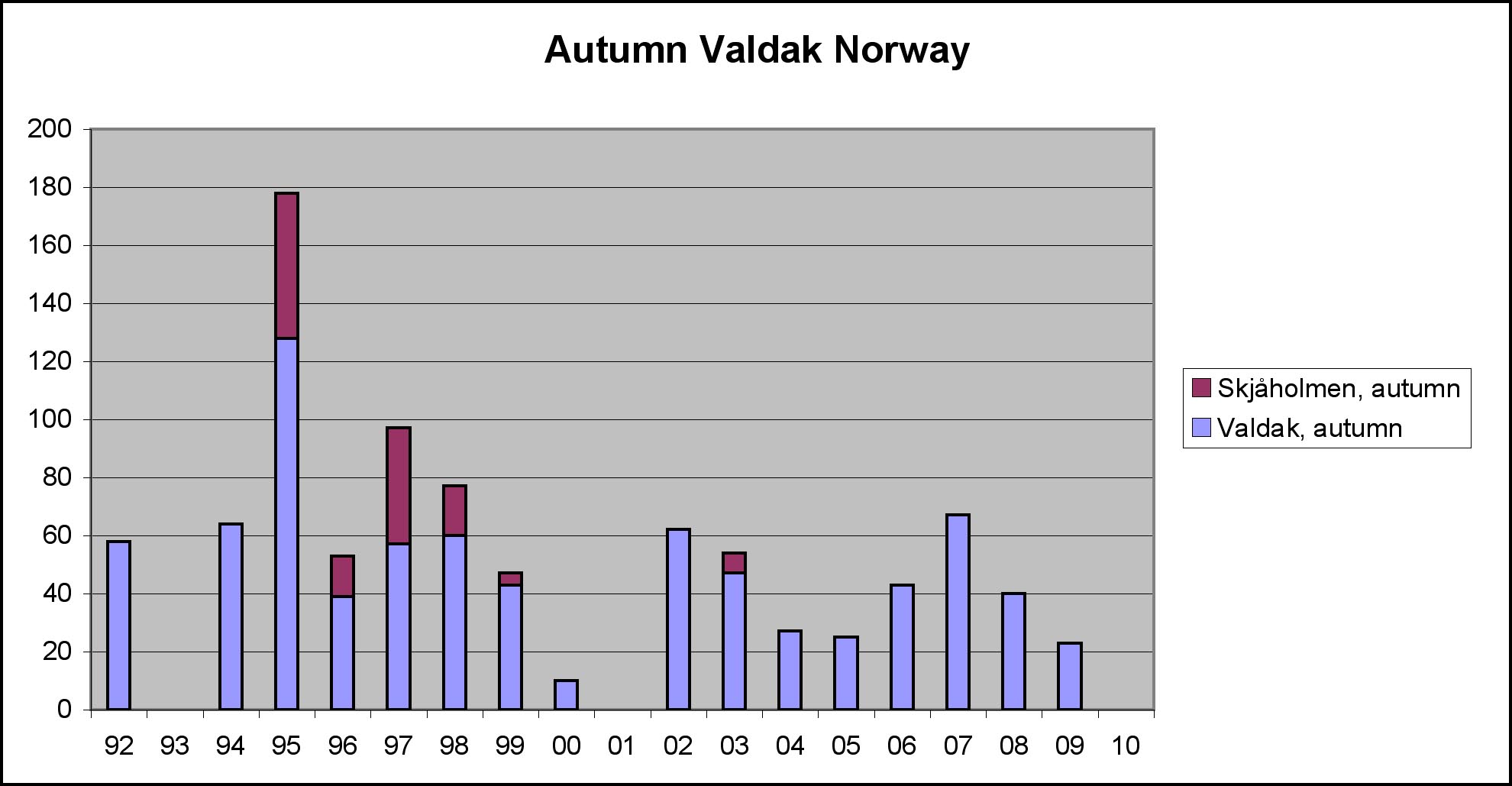

Information on the important spring 2009 count at Porsangen Fiord is not publisehd, but we have the autumn 2009 data. In comparison with 2008 half of the number was observed: 23 individuals, among them 10 young in 3 broods. Probably many adults have flown to the East for moult, having failed in breeding or not bred at all.

Autumn observations of LWfG in Norway.

The birds observed in August in Norway succeeded in flying to Hungary, where - up to one - all were counted at Hortobágy in October.

At present, by the end of 2009, Norwegian LWfG are again seen in Greece. Due to a flood, counting is difficult, but there is preliminary information of some 25-35 individuals. Since only 22 were seen in Hungary, some of them must have come from somewhere else, presumably from Russia or from Norway via the eastern moult route.

Mid winter observations Lake Kerkini, Greece.

Åke Andersson

Vi hade många ungkullar i fjällen när vi inventerade. Summa 11 stycken med över 30 ungar. Det bästa resultatet någonsin. Hittills har fem kullar med sammanlagt 16 ungfåglar kommit till Hudiksvall. Vi hoppas att flera kommer. I Hudiksvall finns nu 71 fjällgäss (16 ungfåglar) och i Sundsvall ca 30 stycken (ingen har granskat dem för att få fram hur många som är ungfåglar). Bland annat har en hona som är 14 år (färgmärkt = utsatt) fått fram 4 ungar.

Vi har 10 nya ungfåglar på gång i Moskva.

Kommer du/ni till mötet på Nordens Ark och/eller till gåskonferensen i Skåne?

Bästa hälsningar.

Åke

ed. Lauri Kahanpää

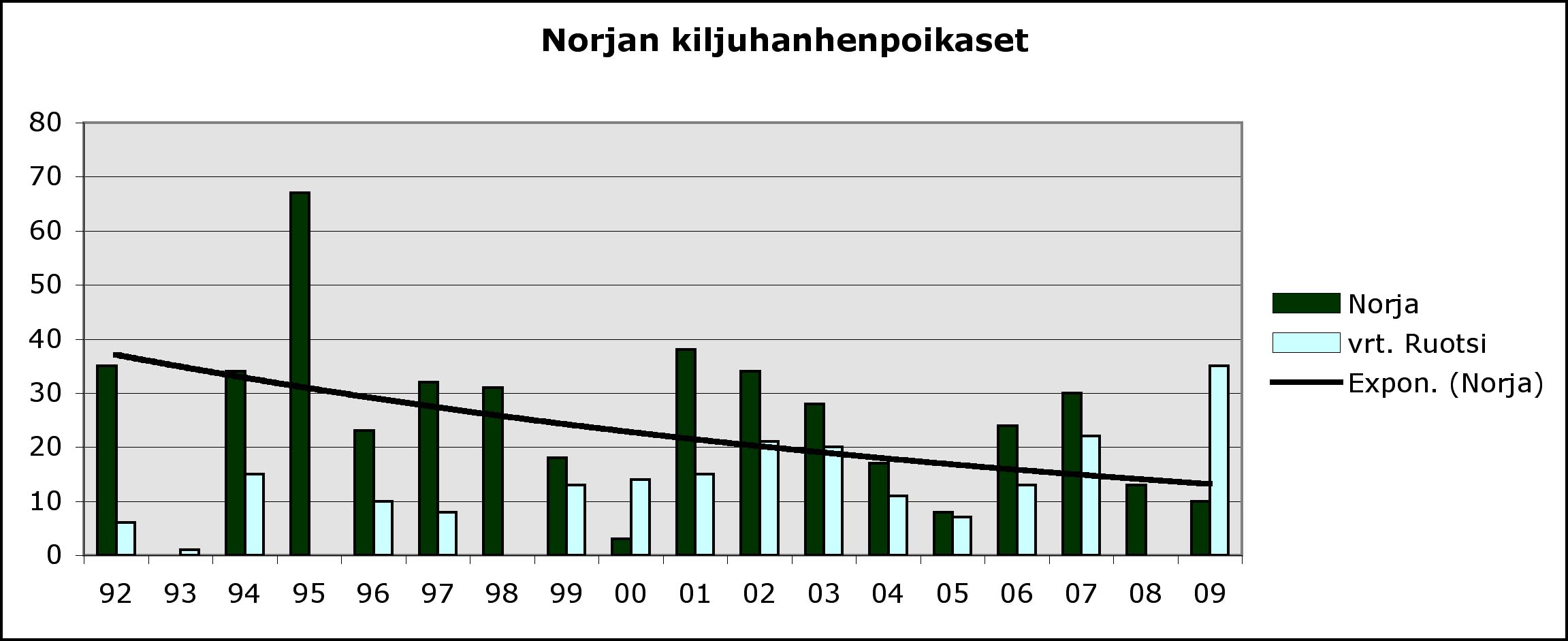

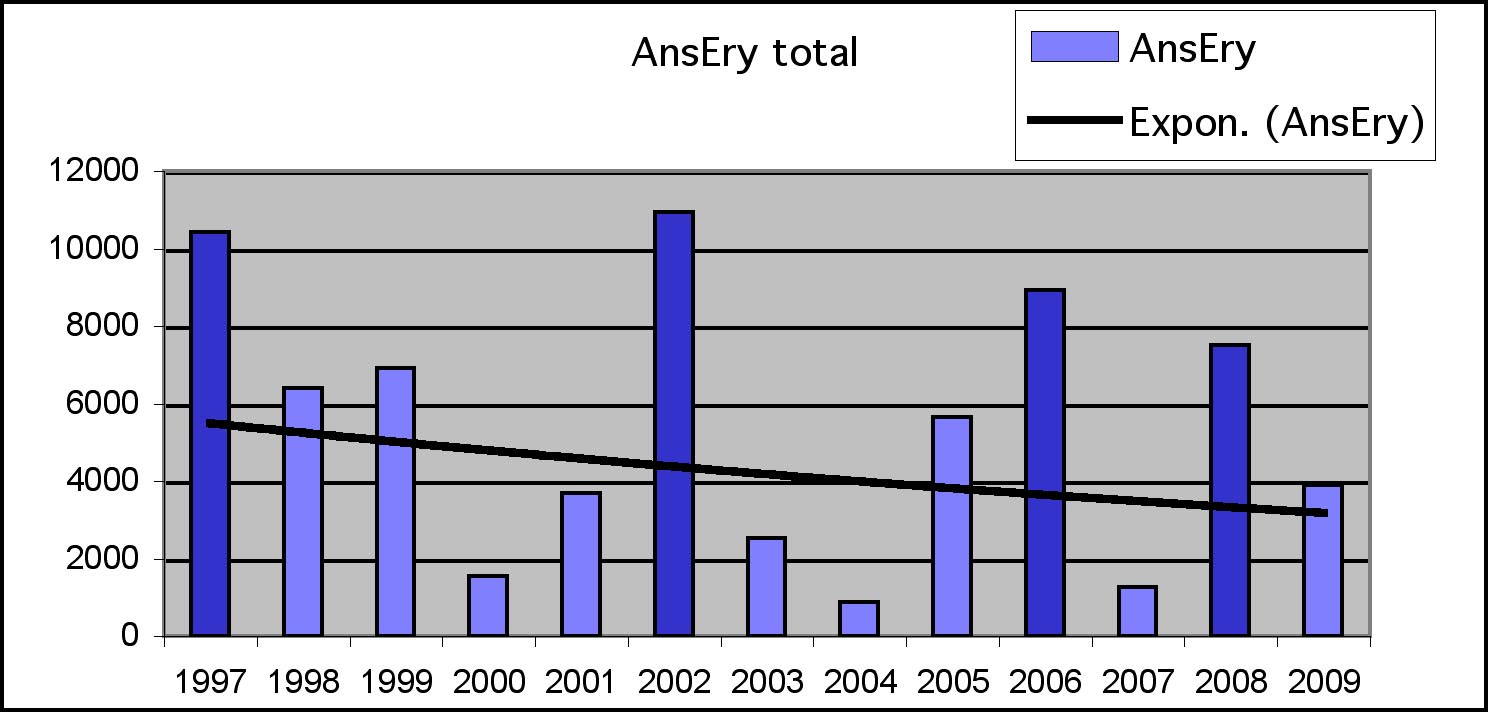

Counted goslings. Releases were interrupted in 1998.

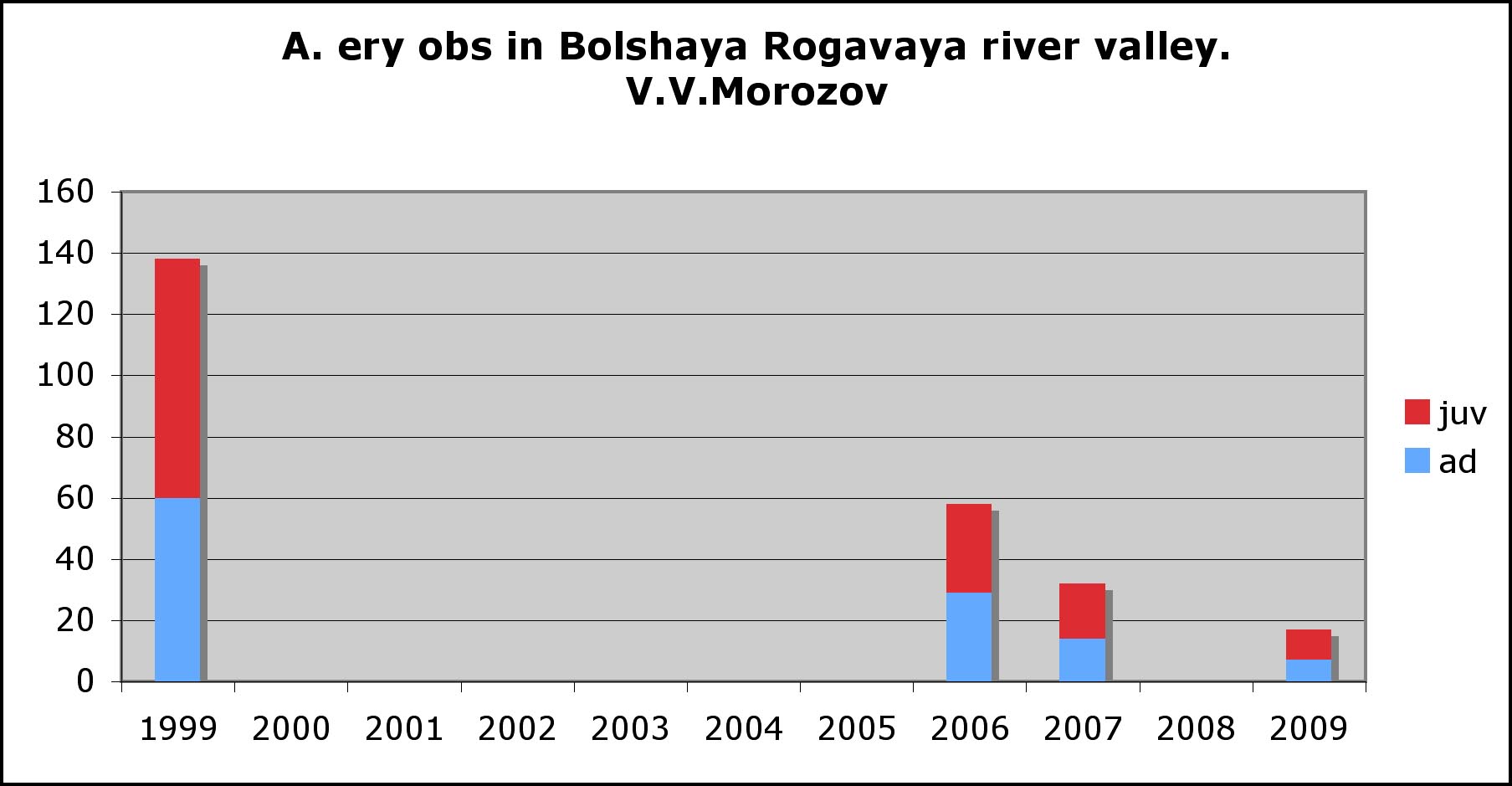

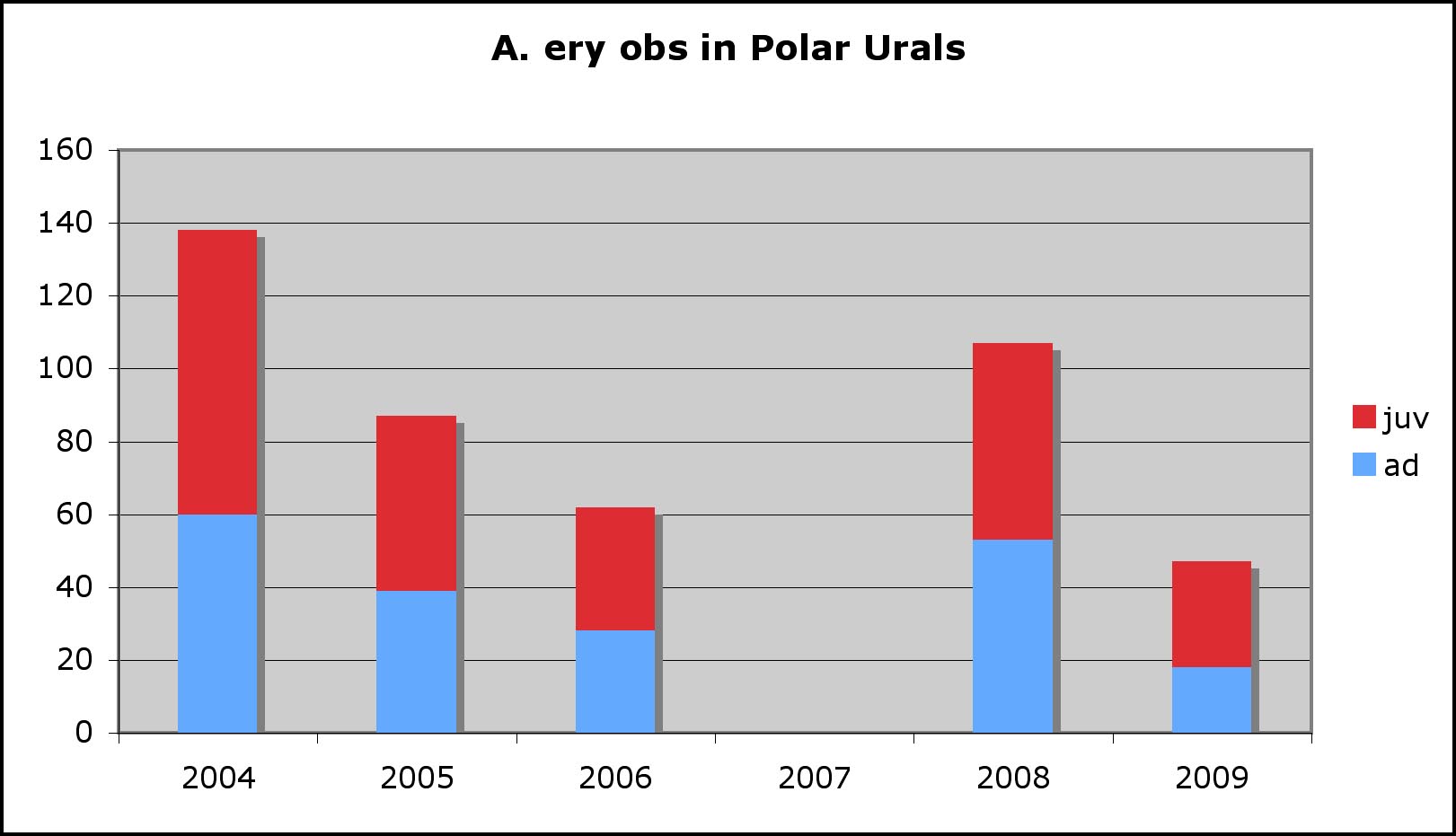

Lauri Kahanpää (Data Vladimir Morozov, E.E. Syroechkovsky Jr., Konstantin Litvin and Oleg Mineev)

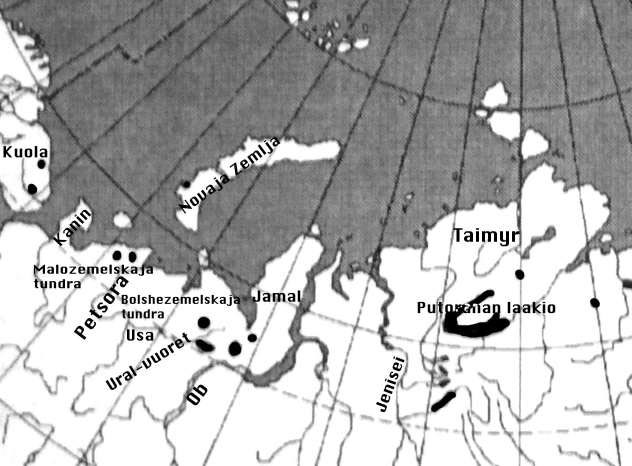

Kola

In autumn, all Norwegian Lesser White-fronted geese begin their migration by flying to the Kanin Penininsula north-east of the White Sea. The only successful count on Kanin was made in 1998. By then about 100 birds were seen, 20 per cent more than were known to have left Norway. The conclusion is that the Kola birds also migrate via Kanin but they are less numerous than the Norwegian.

All in all, there is no reason to believe in more LWfG breedings in Kola than in Norway.

On the Ural slopes, the population was observed to be as viable as in the 1980:s when the last observations had beeen made. Morozov's counts were redone in 2000, 2001 and 2004 and recently updated again. In the new counts, no dramatic change was observed, LWfG still breed on the lower slopes of the Polar Urals. Morozov's estimate for the total number of European Russian LWfG is up to 800 autumn individuals corresponding to 200-300 breeding pairs.

In the years 2006-2009 some 40 LWfG goslings were caught in the Polar Ural area for the Swedish restocking programme. In spite of the difficulties in finding and catching goslings, no eggs were taken, since half incubated are extremely sensitive. Also only two goslings were taken from each brood. Probably catching will be interrupted. It is very exspensive both in money and in lost European free-living Lesser White-fronted Geese.

The Asian side

Talks and abstracts by S. Yerokhov, O. Mineev, V. Morozov and S. Rozenfeld at the GOOSE 2009-Conference at Höllviken, Sweden (by Wetlands International).

Antti Haapanen and Lauri Kahanpää

Wetlands International's Goose Specialist Group held their annual meeting GOOSE 2009 in October 2009 in Höllviken near Falsterbo, Scania, the southernmost point in Sweden. At this traditional meeting, we represented the Friends of the Lesser White-fronted Goose. We listened to 65 talks and distributed 90 copies of our Conservation Plan to the Goose Specialists. Other Finns at the meeting were P. Tolvanen (WWF) and Nina Mikander, the LWfG secretary of the AEWA. The emphasis of the meeting was on the Bean Goose and on (too?) large goose populations causing problems like crop damage. The following lines contain some impressions of talks that we found most important or interesting. Since they deserve their own story, the talks about Russian LWfG were already referred to above.

The site fidelity of the LWfG

In Sweden, LWfG generally breed on small islands in mountain lakes, where they arrive before the snow melts. They find food in nearby marshes. They are not extremely shy; from some of the nesting sites they in fact can see a daily used tourist hiking path. Fishermen and motor vehicles are harmful anyway.

Western migration of Lesser White-fronted Geese

In our Bulletin 4/2008 details on the western migration of the LWfG were already given. Here some more evidence, presented at GOOSE 2009 (J. Mooij)

Already in Sergei N. Alphéraky's (1850-1918) great "The Geese of Europe and Asia. (London, Rowland Ward. 1905)" the Greeater and lesser White-fronted Goose are treated separatelysnd their breeding and mwintering areas are described in detail.

Alphéraky's map on the breeding and wintering areas of the LWfG. The following maps are updated versions of the corresponding ones in Bulletin 4/08 (Thomas Heinicke and Johan Mooij).

19th century.

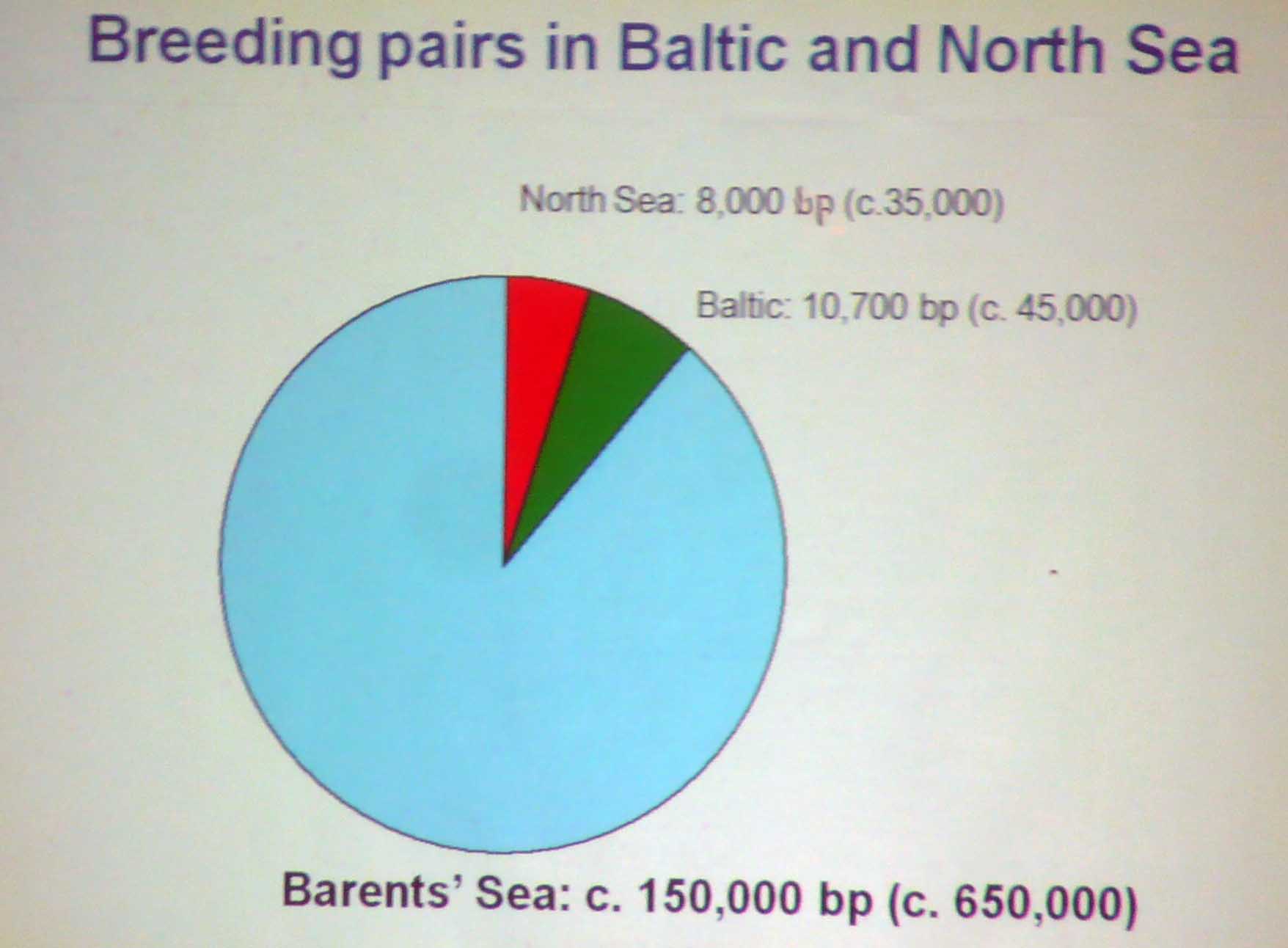

Numbers of Barnacle Geese

J. Karagitseva and H. van der Jeugd described the phenomenal increase of numbers and breeding range of the Barnacle Goose after having been almost as rare as the LWfG. The interruption of the Cold War nuclear tests on Novaja Zemlja cannot explain it all. The species seems to have adapted new strategies, and is currently not only spreading to the Baltic but also numerously breeding in the wintering areas by the North Sea while the main population keeps on expanding in the Russian Arctic.

The main population still breeds in the arctic, but the fastest growth is by the North Sea

Neozoic geese

Recently introduced species of geese are monitored in Germany in projects described in the talk by S. Homma and O. Geiter. More than 8000 have been ring marked, including 6000 Canada Geese. More than 100 000 observations are made. Most species have no significant effects on the ecosystem since they never established. Some are successful. If breeding goes on for 25 years and 3 generations, these acquire the same legal status as autochlon species. Such are in order of population size:

- Graylag Goose (Anser anser)

- Canada Goose (Branta canadensis)

- Egyptian Goose (Alopochen aegyptiacus)

- Barnacle Goose (Branta leucopsis) has autochlon and neozoan populations

- Swan Goose (Anser cygnoides)

- Snow Goose (Anser caerulescens)

- Bar-headed Goose (Anser indicus)

In Germany, the Canada Goose is increasing rather fast but only slowly widening its breeding range, which leads to high densities inside - much like Andersson describes the LWfG in Sweden. (Only, German Canada Geese do not migrate at all.)

In France, the Canada Geese have increased in 10 years from about 1000 to about 5000 individuals corresponding to 1000 breeding pairs. Crop damage and hygienic problems are reported and the population is now somewhat controlled by infertilizing eggs etc. (C. Fouque and V. Schricke)

Cao Lei and Mark Barter gave three interesting talks on Geese, in particular LWfG wintering in China. The whole population gathers at East Dongting Lake. The threats are obvious, the area is the same where more than a thousand were poisoned to death come years ago. The more technical part of their talk was about LWfG feeding behaviour and habitat use in winter.

Pentti Alho

This winter came early, but luckily we have cleaned the cages in time before freezing. Actually, the large hall would still neeed a few tons of fresh sand but taking the dirt away under freezing conditions is not so easy. Last year we did not manage to change the sand on the whole area and that had some effect on the geese. There is a clear correlation between the hygienic status of the farm and the health of the birds. The size of our captive population has not grown since the catastrophe (we lost 50) in 2005. This is partly because unfortunately the best producing birds were killed in the snow storm, partly to the annual loss of stock by releasing goslings into nature.

In spite of the 200 square meters of obstacle tarpaulins, geese still get killed by flying against the cage walls. Our experimental cutting of wing feathers of some birds seems not to have brought any improvement, but there still is not enough data for final conclusions. The productivity of arctic geese like Lesser White-fronted in captivity is annoyingly low. This must be taken into account when planning for the future - something that is done in thecomputer model Effects.xls. It is of vital importance to increase the captive population. If that fails, there will not be enough goslings to be released - a problem that marred the original Swedish and Finnish preojects in the 1980s as well.

A second breeding site would be very welcome but no such development is in sight. The only chance for a quick partial soluton could be cooperation with some zoo, maybe Ähtäri or Ranua. Another bottleneck is the need for a few helping hands on the farm, in particular during breeding time in April and May. Managing alone is becoming impossible.

Jyrki Patomäki

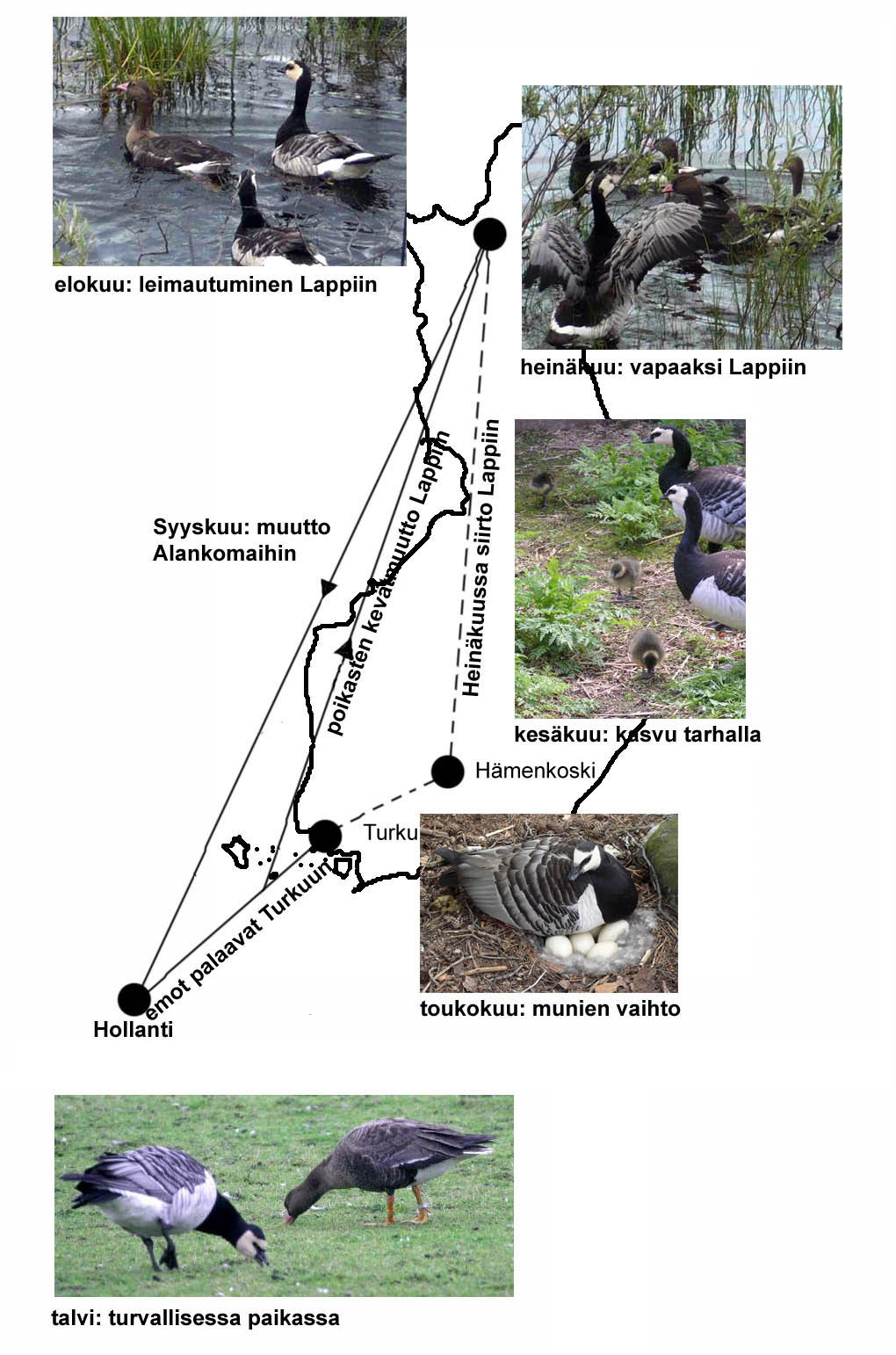

and taken to the farm

where the foster parents take care of their offspring until they are almost ready to fly.

Now they are ring marked or even satellite tagged.

Next, they are transported to the release site in lapland, far North of the Polar circle, where the Lesser White-fronted Geese will hopefully breed later.

Although the Barnacle Geese now are released in a totally unfamiliar place, more than 1000 km away from where they were caught, they will in autumn fly their traditional wintering areas - to the Netherlands. The juvenile Lesser White-fronted Geese follow their foster parents and are in theprocess imprinted on this migration route. In spring, the juveniles return to Lapland but their foster parents return to their original nest.

Imprinting on the parents and imprinting on their species are completely separate processes (Cf. I. Koivisto in 4/08). Therefore it seldom happens that the LWfG goslings are imprinted on the species Barnacle Goose and later hybridize with these birds. In the few cases when this has happened, mixed pairs have never been observed in Lapland, only in south Sweden and possibly south Finland.Hybrids between various goose species are not uncommon in nature (E. M. McCarthy 2006, Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World. Oxford University Press. 583 pp), but hybrids of the next generation are extremely rare. In fact, most hybrids are infertile like the mule. This means, their chromosomes do not fit together. In addition to that, hybrids do not respond correctly to the pairing rituals of either of their parent species, so they almost never even get a chance to test their chromosomes. Therefore, the main disadvantage caused by the occasional mis-imprintings is the loss of potential Lesser White-fronted Geese from the project population. I guess, nobody will seriously consider the loss of one potential Barnacle Goose a threat to that species!

The difference in breeding success is sometimes interpreted as indicating genetic poor quality of the Swedish reintroduced birds. The above explains the phenomenon away. In fact, the released birds have ancestors in several captive populations across western Europe. A genetically diverse background is favorable for reproductionin the long run, a fact that was often observed when restocking natural populations with zoo individuals. What happens is first a diversification or the genomes in the now free-living population. Out of this abundant supply, natural selection is now offered the chance to pick out the most favourable combinations for further reproduction. In the Swedish reintroduced population such trends are already visible; after the interruption in releases, the population was almost stable for a while but is now growing with an incresing rate.

Could the same happen "naturally" in Norway? Evidently, the young fenales of the Norwegian population often find "alien" Siberian partners in winte; one should keep in mind that juveniles in their second winter will generally migrate for moult to the east, possibly all the way to Taimyr. So there must exist a strong genetic flow from Russia to Norway - something that was detected in genetic studies as well. But this situation is different from the Swedish one. There is less reason to believe in an accumulation of favourable genes in Norway. Because of the small size of the original population, almost all females will pick up foreign partners, and the gene flow may already be so strong that it will wipe out all original gene combinations before they have had time to mix with the new-comers. The best combnations will not have time to be selected. As a result, the Norwegian birds may already be infected with genes giving them the drive to migrate absurdly far to the east, maybe to breed in a too open habitat or some other property very useful in Siberia but possibly not at all in Lapland..

Antti Haapanen and Lauri Kahanpää

The Finnish LWfG reintroduction programme suffers under the lack of Barnacle Goose foster parents. The reason for this problem is that our permits to catch new foster parents have laid for years in the files of various Administrative Courts delayed by complaints sent by local units of Finnish BirdLife. We only have few from earlier catching. In spring 2009 two pairs begun breeding in the correct time in relation to the breeding of our captive LWfGs but unfortunately one of these breeding failed because of extreme weather conditions.

Fig. 1. The transmitter weighing 18 grams would fall off in about one year as the harness breaks down in daylight. So in 2009 we were able to release only one family. The Barnacle Goose female was equipped with a satellite transmitter. We hoped to follow their movements and especially the migration south July 20 the birds were released in a good habitat close to the forest limit in Finnish Lapland. We were daily able to record the movements of the family with an accuracy of 100 meters. About ten days later, a local fisherman happened to see the unexpected birds photographed them and took the picture to the local BirdLife for identification.

From August 9 on, the satellite information showed that the transmitter had ceased to move. We checked the area on our maps and on Google Earth, and it looked like peat land with small ponds. Later it turned out that the satellite pictures must have been created in spring or after heavy rainfall; in reality it was rather some upland birch wood habitat and not at all a site where you would expect to find geese. So we sent our own expedition to find out what had happened. They found remnants and the rings of our Barnacle Goose female but did not find a fresh cadaver or the expensive transmitter. (See their report in this bulletin.)

Fig. 3. A weird view on Nature Conservation? The transmitter was programmed to function in different hours of the day and it took a month until it was operating in daylight. September 12 we send another group to inspect the place and to search for the satellite transmitter. They had appropriate equipment. A handheld yagi antenna was designed and built by dr. Pekka Kekäläinen at the department of physics, Univ. of Jyväskylä, and EVP-Tekniikka company provided a pocket size radio receiver capable to hear the very special frequency.

Tiedettä, tekniikkaa ja käsityötä Using these tools the radio transmitter which had been on the back of the female Barnacle Goose was found in a couple of hours not far from where the rings had lain.

In late September we got to know from a private person that already in late August the Environmental Center of Lapland had given some Natural Heritage Service rangers the permit to eliminate the Barnacle Geese foster parents by shooting and the LWfG goslings by catching and taking them back to our farm. Neither we nor our research partner, Jyväskylä University, were informed by the officials.

In addition to this we learned that the Environmental Centre had asked the local police to inspect whether alien/exotic species had been released into nature by us. The first author of this article took contact to the police clarifying the question whether the Barnacle Goose is an alien/exotic species in Lapland whose release could be in conflict with the Finnish Nature Conservation Act. The Barnacle Goose is no such species. On one hand, it has naturally extended its breeding range into Finland and is now, equally naturally, more and more often also seen in Lapland. On the other hand, our project does not interact with this process in any way since long term observations in Sweden prove that the foster parents never return to Lapland next year. They return to their former breeding area, usually to the same nest where they were caught. Also, they were under satellite control.

In a similar case in 2005, our goose breeder Pentti Alho was sued in 2005. The year before, we had released one family with Barnacle Geese as foster parents and LWfG goslings. By that time we were accused on the release of the LWfG goslings as alien/exotic species. The prosecution failed. This is important since there is a basic juridical principle: after a court decision has reached the legally binding status, you cannot prosecute repeatedly on the case which already was decided upon. The police inspection papers of the present case are now in the hands of the local prosecutor. She has promised to decide before midsummer 2010 if she will take the case into court. We have informed her that we welcome a quick decision before continuing nature conservation activities.

So absurd is the situation of nature conservation in Finland! We know who are responsible for this and the earlier (see the leading article) abnormal behaviour of the nature conservation officials. But it is hard to understand their motives.

Erkki Jaanu

I called Eero Peltonen. We decided not to loose time but travel to the place to inspect what has happened before the bird, or cadaver, would disappear. One way's driving to there is about 1100 km. Erkki Kellomäki provided us with the ARGOS coordinates of the last localization of the site. I rented a GPS and received a 5 minutes instruction course on how to use it. The first leg of my trip took me a few hundred kilometres to Viitasaari to join Eero in his summer home. Having spent the night there we started for Enontekiö, the commune in Lapland where the geese were released. On the way we had breakfast with pancakes and coffee and in southern Lapland, by the famous Tornio salmon river on the border with Sweden, we ate whitefish soup for lunch - the Kukkolankoski rapids are famous on their whitefish. At five o´clock we arrived in Enontekiö. On the way we had admired Eero´s brand new navigation set. We did not need it for navigation, however it gave us useful ''obs!'' signals which might have had something to do with our nice and quick rideOnce we parked, the GPS-device was turned on. It showed the distance of 1,8 km but we noticed the batteries are getting out. No problem. We ate a little of our sandwiches and the batteries were loaded in the car. So we started the hike. I read the map and compass and Eero followed on the GPS device how fast we were approaching the site given by satellites. First the terrain was bushy and wet and later in addition stony. Having climbed uphill for a while we reached the alpine birch woodland, easy to walk. We went a little bit too much to the right but that lead to an interesting observation: we stumbled on a World War Two gun station and old scrap which showed that the guns had been used on the site.

We took a corrected direction. The GPS showed the distance converging to zero. And finally it was zero. There we left our knapsacks and lifted a white plastic bag in a mountain birch as a beacon. We made observations around this zero point. I checked the stones and their surroundings without any findings. After a while we met with Eero in the zero point. Eero had found one of the colour rings and some feathers. Some of the feathers were on a sharp stone and some around it. Apparently a fox had tried to dig in the dead bird as mosses were thrown around. The feathers were bitten. A small piece of trachea was found, too.

No goose habitat! Since the stone was not a place were a fox would eat its prey we concluded that also some bird of prey had taken part of this prey. We made further surveys and found two more rings. All three rings of one leg were found. The metal ring and one colour ring of the other leg were not found. No signs of a fox den were found. After all we decided that we cannot find the small dark gray radio transmitter without a special antenna. We decided to leave the place. We dicovered a smooth path downhill. At 22 o´clock we were back by the car. The sun was still shining. A fox was running along the road.

After a night in a tent we visited the releasing site. The water level was low. A young Hen Harrier rose from shore line stones and a duck family was hiding in the willow bushes.

Back home in the south (!) the waterfowl and the gulls are breeding only in places surrounded by water. Apparently the same holds true in the north, too. According to Åke Andersson the LWfG in Sweden breed on small islands. The Barnacle Goose is a good foster parent aggressively defending its young. This behaviour may be its weak point in areas where the Red Fox has become fairly common. This is the case in most of Lapland, where the Arctic Fox is close to extinction. Should we find a safer releasing site?

EVP-tekniikka

Lämpöura Ky Pentti Tenhunen

Pirkanmaan lintutieteellinen yhdistys ry.

Hämeenlinnan Raatikuva Ky Heikki Löflund

< lauri.v.kahanpaa@jyu.fi> Technical update done Mar 10 2010