Negotiating new reading conventions

From Erasmus in the Sixteenth Century to Elizabeth Eisenstein in the Twentieth, almost every scholar who has grappled with the question of what reading does to one’s habits of mind has concluded that the process encourages rationality; that the sequential, propositional character of the written word fosters what Walter Ong calls the ”analytic management of knowledge.” Postman [”Reading”, Victory Garden]

Read, read, read, read, my unlearned Reader! Tristram Shandy [”Almosting It”, Victory Garden]

The conventions governing the reading of books have formed through centuries. These conventions have become such automatised parts of the reading process that usually they are not even noticed, and one does not need to paid attention to them. With digital texts, however, such conventions have not yet been formed. When confronting them, the first task for the reader is to learn the rules governing their reading.

The authors of digital texts, who have often started with traditional texts, understand the problematic situation very well, and thus offer the readers specific reading instructions. Additionally, at least in this transitory phase, digital texts very often include metatextual materials commenting on the text’s own functioning, and that way provide implicit instructions. Despite these helping tools, the reader naturally has also to rely on the old method of trial and error, learning by doing.

User instructions can be seen to belong to the field of paratexts, which also includes such text types as cover texts, author introductions in the flaps, liability notices (”all resemblance to persons living or dead…”), contents tables etc[1]. User instructions are divided to two sections: technical instructions which closely resemble all software user instructions, and instructions which familiarise the reader with the signification processes in the text content.

Installing Instructions

Technical instructions usually tell how the text should be installed to the computer and how the program then should be started – that is, they tell what one has to do to get the text available at all. With Internet texts there usually is no need for installation, but quite often one or more plug-ins for the browser is needed, and the location of the plug-ins is told in the technical instructions instead. In Stuart Moulthrop’s Reagan Library, below the subtitle ”Technical”, it is told that the text requires a QuickTime VR plug-in, and an address where it can be downloaded from. Even though the installation process most often is very simple, this step has important implications for the reading process. Installation clearly stands out as an external, technical operation, which, as a requirement for reading aimed at make believe and pleasure, easily turns into an unnecessarily annoying obstacle on the way to the world of digital texts. Development naturally goes to the direction where the installation will be more and more automatised and probably – especially thanks to the electronic reading devices, ebooks – totally got rid of. The installation phase cannot, however, be just ignored, for at the moment it is an unavoidable precondition of reading digital texts, and as such it will affect people’s expectations and experiences of them – and further, this effect may still linger in people’s minds even after the installation process has vanished as unnecessary step – the change in opinions is slower than the progress in software development. As a preliminary notion we can expect that the installation process attunes the reader to the level of a certain intellectual challenge, which may, in its turn, have the consequence that reading digital texts weighs more the rational aspects, compared to the traditional texts weighing the emotional aspects.

And as is common in the software packages, Eastgate Systems offers for the readers of their hyperfiction also product support:

If you have any questions or problems, our support staff would be delighted to help! Just call us at: (800) 562-1638, or write to: Eastgate Systems…[2]

There is also an interesting addition in the instructions:”We can supply critical studies and pedagogical materials for most hypertexts we publish.” Here we can easily see an inscribed implicit readership: an academic audience who is interested in criticism and whose interest in hyperfiction, partially at least, is theoretical. What is also important here is the foregrounding of pedagogics: hyperfiction serves as a pedagogical tool for both those who study writing (creative or technical), and those who are interested in the theory of fiction.

Interface

In addition to the installation instructions, the technical instructions also teach the reader to navigate in the hypertext, to use its interface. With certain hypertext environments these procedures are more or less stabilised. Hypertexts written with Hyper Card or Story Space editors, for example, usually employ one basic interface model (with slight variations, though) – the same instructions apply to any hypertexts written with Story Space. Usually these instructions are included in a leaflet accompanying the disk, that is, in print text, sometimes also in the digital text itself. Because of the potentially huge variety of digital text types, it is not probable that any one interface solution would become dominant, but each text type is likely to develop its own standards. On the other hand, it is also probable that because of the dynamic nature of digital texts, there will always be unique interface solutions not confirming to any possible standards. In the present situation with several rapidly developing interface models – and new ones coming out all the time – the reader has to learn the interface with each new text up from a scratch. This is an unhappy situation for the reader, and one necessarily strengthening the estranging effects of digital literature – but on the other hand, this situation offers a unique possibility to scrutinise the effect of interface on reading: with traditional print novels the interface is already so naturalised and automatised that it is very hard, if not impossible, to study its effects as such. The originator of cybertext theory, Espen Aarseth, has stressed the point that cybertext is a perspective on all literature, a perspective from which the material and functional aspects of texts are foregrounded – as such it can be well seen as an answer to the need for theory which accounts for the ”technological nature” of book, expressed by Ronald Sukenick already in early seventies[3]. We might even claim that the study of this technological nature of book has not been really possible before we had the necessary background provided by digital texts.

Traversing the hypertext involves a few basic problems which must be explained to the reader.

Because Afternoon is a hypertext, it invites you to take an active part.

- You may move through the story by pressing the Return key to go from one screen to another

- You may double-click any word in the text to follow various lines of the story. Some especially significant words yield, bringing you to a new line of the story. Others continue the current thread.

First, in hypertext each lexia may have a default link, with which the author may provide the reader some provisional paths through the textual network, or alternatively, the reader has to make an active selection after reading each lexia, to select the particular link she wants to follow. The links leading away from any lexia may be presented in many ways: the anchor word/phrase may be indicated by a specific font type, or the links may be listed in a separate link list (also the links leading to that particular lexia may be listed this way). Also, different navigational tools may be employed, like history list with which the reader may return to previously read lexia etc. Several links may be chained together, to form paths which make it possible to locally follow specific narrative strands. All these options are related to the essential property of hypertext, namely that the reader may choose her own way in the textual net: each of the lexias include a link or links leading further away from it, and a patch of links may form a more or less coherent path. The reader has to learn how to find the links, and how to follow them: clicking the underlined or otherwise indicated words, pressing certain keys causes the anchorwords to be indicated (by framing them or otherwise), using separate link lists, getting the link list appear by pressing certain keys or buttons etc. In a link list each link may be titled, and all links with the same title belong to the same path; furthermore, the link list may also provide the titles of the destination lexias. Thus, after reading a lexia the reader may follow the default link (if one is provided; this closely resembles turning the page); click an indicated anchor word; click a word she assumes to work as an anchor (if the anchors are not indicated at all, as in Afternoon[4]); select a link from a link list; open a link list and choose one according to its title or destination; or, backtrack to the lexia previously read.

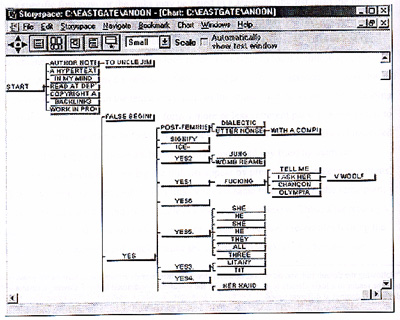

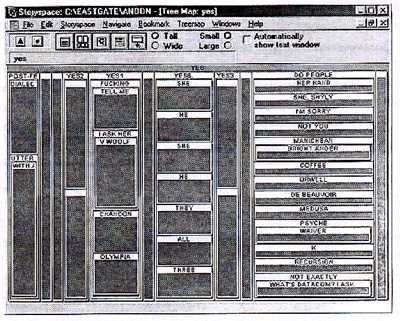

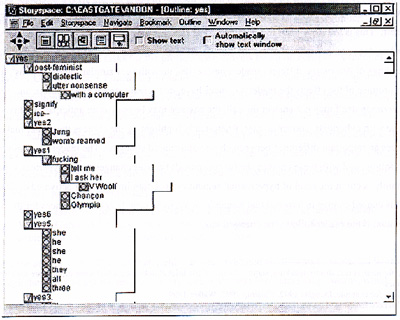

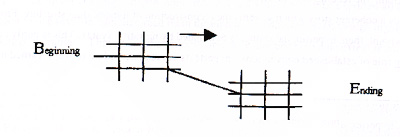

The next option the interface may offer to the reader is to present the hypertextual structure in the form of various cognitive maps. These help the reader get an understanding of the inner structure of the text, and she may also choose her path directly on the basis of the map. Hypertext may be presented as a three-dimensional network, in which the reader may choose one of the lexias in the present level, or go to a lower (or upper) level – the similarity with embedding levels of narratives is obvious but misleading; these two structures do not necessarily coincide at all. First, the reader has to learn to use the map, learn how to go from a lexia to another, and from one level to another. After that she may try to find out in what exact relation the hypertextual structure stands to the narrative structure.

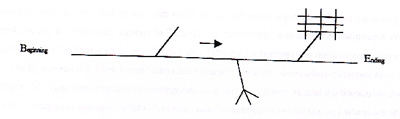

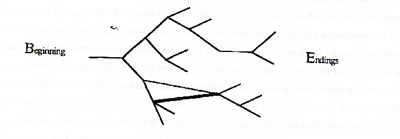

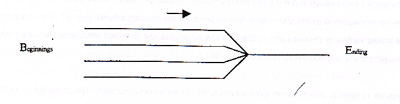

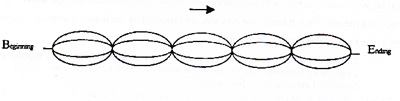

Different ways to visualise the

hypertext structure in Story Space

”Reading Instructions”

There are not only technically oriented instructions with hypertexts, but usually also some kind of hints about how the textual signification structures should be interpreted. As a good example we can take Michael Joyce’s explanation of the ideas underlying Afternoon.

The story exists at several levels; the story changes depending on decisions you make. A screen you have read before may lead to something unfamiliar, because of a choice you make, or choices you have made on other screens of that reading. There is no indication of which words yield; but they are often character names, pronouns, and words which seem particularly interesting.

This passage contains two important things. First, ”the story changes depending on decisions you make”; and in close relation to this, one link may lead to different destinations depending on the reader’s previous choices. The claim (or promise) that the reader’s decisions have an impact on the story itself has a strong effect on the reading experience – it raises expectations which are then, to some extent, turned down. As long as we are dealing with closed (and relatively small) static hypertexts, there is always a saturation point where further reading does not, in any significant way, change the text any more.[5] Simply put we can say that Afternoon is an aggregate of variations of a story (it is, naturally, impossible to formally draw a line where a variation turns into a new story), but the readers have a tendency to fuse the variations into a whole – or as it is said in the text itself:”This is the story itself in long lines.” The fact that parts of the story may be read in various orders does not, in practice, affect the story itself at all - this can be seen in comparing different readings of Afternoon: different readers have ended up with very similar interpretations[6]. This kind of promise of the effects the reader’s choices have, does create strong expectations, and even if Afternoon itself may not answer the call, the passage may be read as an anticipation: this will be the case with cybertexts, sooner or later. Rhetorically highlighting the choices the reader makes, Joyce hides an important difference between chosen and caused changes[7]. The reader chooses what links to follow, and with these choices she (unconsciously) causes changes to the hypertext – the changes mainly occur at the level of hypertextual semantics: a certain link is either activated or deactivated. This caused change in hypertextual semantics may, in its turn, bear consequences for the narrative syntax, if the reader follows the changed link.

In the instructions to Afternoon, then, the reader is told that her choices affect the text, but she has no way of knowing what happens and when. This may induce a certain sense of paranoia, easily present with hypertexts: the reader often has a feeling that there are things she doesn’t know about the text, that on the brinks of the field she has gone through there lurk links not investigated, links that may lead to information vital for the whole text. Awareness of the fact that every choice she makes may close some paths for good just strengthens the feeling of being at the mercy of the text.

It is simply that there is more to know, all these indices pointing somewhere, and the thing becomes a web. You feel a vibration as something snags itself and then crawl, tortuously, expectantly out to the margins. – It is like music, when you write like this, all the interconnected notes, the counterpoint. (”Speak Memory”)

When hyperfictions get larger (without limits in Internet) and their functioning more complex (the choices several readers make, unconscious of each other, may cause the text to organise according to a totally new set of rules etc.) the actual situation is more and more out of the reader’s control – in this view current hyperfiction offers a soft landing to the world of cybertexts proper.

But then, we have similar experiences with print literature too. One of the underlying principles of Vladimir Nabokov’s oeuvre (one element of its thematic dominant, according to Pekka Tammi (1985)) is the idea that everything is connected, and only art may unveil these connections. As a consequence Nabokov’s texts always seem to contain implicit connections which can never be fully mapped (notice the Nabokov reference in the title of the lexia cited above). Quite a similar experience prevails in Thomas Pynchon’s novels, in which the finding and mapping of the connections is one of the central tasks for the protagonists. Novels based on conspiracy theories, after the style of Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum, contain many similar elements, but they present the connections more directly as created or maintained by certain specific instances. Despite the apparent similarity, there is a clear qualitative difference in hyperfiction: the reader’s own choices cause changes in the text and thus she is drawn into the network of connections, causes, and consequences. While the reading instructions stress the role of intentional reading, the reader as a conscious participant in the meaning production, the unconscious or unintentional participation is presented implicitly, and even, menacingly.

Victory Garden’s pathways and links are complex and subtle, but never random. Victory Garden keeps track of your path through the novel, and takes your previous choices into account when choosing a path to follow.

In Afternoon the anchor words (”words that yield”) are not indicated at all – this is explained by the author through the desire to get the reader actively seek in the text for ”interesting” words, which she may assume to work as anchors. This helps to build up another strong frame of expectations: links are related to ”interesting” things.

There are almost always options, wherever you are reading. The lack of clear signals is not an attempt to vex you, but rather an invitation to read inquisitively, playfully or at depth. Click on words that interest or invite you. (Afternoon)

In reading instructions such things are also included, as references to where texts begin and when/where they end:

Closure is, as in any fiction, a suspect quality, although here it is made manifest […] (Afternoon, ”Work in progress”)

[T]here is an end to everything, to any mystery, (Afternoon, ”yes”)

… not as cockroach… there is no mystery, really, about the truth. You merely need to backtrack, or take other paths. Usually the silent characters yield what the investigator needs to know. – It isn’t over yet, by any means, this story. (Afternoon, ”then I woke”)

The citations above take up the difficulty of ending in hyperfiction – that stories need endings, that a place looking as an ending point does not necessarily mean the end.

Finally, we can count into reading instructions the sentences addressed to the readers, in which she is given a role in the fictional world. In the beginning of M. D. Coverley’s Califia, for example, the reader is given the role of a treasure (co)hunter – reading is thus equated with treasure hunting, and ”finding one’s own path”.

We are seeking assistance in discovering the possible location of a stash of gold. […] Calvin, suspecting we might have overlooked some obvious link or are missing extant information, suggested we invite interested parties to contribute. (”To the Reader”)

Also the lexia and path titles give the reader information about how these lexias and paths relate to the text as a whole – they do not differ, as such, too much from chapter titles in traditional literature, but there quite simply is so much more of titles in hyperfiction that their role in giving information is more significant.[8]

The amount of metafictional materials in hyperfiction is striking. This can be mainly explained by the novelty and short history of hyperfiction – since there are no established conventions yet the authors have to put much effort on pondering questions related to the crucial apects of this new medium – the lack of established conventions, then, is not only a problem for the audience, but also, and even to a greater extent, to hyperfiction authors. In this sense we can accept the claim that authors and readers have come closer together: they both participate in the construction of this new textuality. The situation can well be compared to the birth of modern novel – Don Quijote is a metafictive novel par excellence, even though Tristram Shandy in its manifold metatextuality is a more apparent point for comparison:

-- for in writing what I have set about, I shall confine myself neither to his rules [Horace’s], nor to any man’s rules that ever lived. To such however as do not choose to go so far back into these things, I can give no better advice than that they skip over the remaining part of this chapter;[…] – Shut the door. – (Sterne 1991, 5-6)

The first explanation for the metafictionality of hyperfiction, then, is the creative chaos preceding the establishment of any new forms[9]. The other explanation is the influence of postmodern fiction which self-consciously breaks the established forms. Hyperfiction can also be seen as an inheritor or evolutionary form of experimental avant garde literature (especially the postmodernist novel and concrete poetry are relevant here). Here we have to note, however, that generally speaking, hyperfiction so far has been much closer to realistic than postmodernist narratives – there are exceptions to this rule, naturally.

In Afternoon one can find a lexia, the content of which is a quotation from Tristram Shandy – it is about a midwife. Even though the passage quoted, as such, is quite insignificant, the midwife nonetheless raises an allusion to Socrate’s notion of philosopher as a midwife for ideas; he just helps people reformulate and bring out the knowledge they themselves already possess. If a jump from Shandy’s midwife to Socrates feels a bit arbitrary, it is backed up by another reference in Afternoon, to Plato’s Phaidon, in which Socrates figures heavily. One way to interpret these allusions is to see it as a comment on the reader’s role in hyperfiction – the author (Joyce) just gives some tools, with the help of which the reader constructs her own story – this interpretation is well in accordance with Joyce’s several theoretical writings where he stresses the active role of the reader.

Metatextuality dealing with hypertext

It is quite common to find lexias dealing directly with hypertext in hyperfictions. Ted Nelson’s definition of hypertext is often discussed, as well as various texts dealing with hypertext and hyperfiction by Joyce, Stuart Moulthrop, Jane Yellowlees Douglas, and Jay David Bolter. Theoretical quotations on their part speak about how the authors continuously have to reflect the limits and consequences of the new mode of writing they have chosen. This way they offer the reader at the same time more or less direct instructions of how hypertext should be treated and used.

Especially the problem of ”ending” has been a subject of extensive metatextual ponderings.

…praying constantly Please Continue… (Victory Garden, ”Talkin’ ’bout the Horror”)

…the possibility of No Return. (Victory Garden, ”National Dick”)

…our grand obsession with Return. (Victory Garden, ”6-10-91”)

All these citations taken from Victory Garden seem to reflect Peter Brook’s notion of narrative logic, in which the ending (and the anticipation of ending) is the driving force, and how the story, however, borns out from the deferral of the ending[10]. And when the text is read through to the end, the reader, in her mind, goes back to the text. Moulthrop deals with these questions in Victory Garden on the level of form, and brings them also to thematic discussion, as in the citations above – the reader does not want the story to finally end, she wants to return back to it over and over again, and still, a return to the same story may never be possible.

The lexia ”then I woke” cited from Afternoon (a few pages earlier) is also metafictionally reflecting the question of ending. The text in this lexia continues seamlessly its title (”Then I woke… not as a cockroach”) and alludes to Kafka’s ”Metamorphosis” – to a story in which the waking from a dream does not, by all means, end the nightmare (story), but begins one.

Jane Yellowlees Douglas has done the most thorough study on the ending and closure of hyperfiction so far[11]. She presents four arguments for her "sense of an ending" in a certain place/ lexia in Afternoon. First, from this lexia there was no default link leading forward. The lack of a default link alone is by no way a satisfying condition for closure - but it hints to the possibility that this place might be an ending point for something. Second, the main narrative tension seems to be solved in this point (the dubious behaviour of the protoganist when he fears he has seen his ex-wife and son to die in a car accident, is explained by the revelation the man himself obviously has caused the accident). Third, most of other narrative tensions seem to be solved too. Fourth, the lexia is "at the bottom" of the hypertextual structure (a systematic reader may detect an embedded hypertextual structure in Afternoon).

The ending may be the biggest single change when going from text to hypertext: the reader has to settle with the fact that there is no definite ending in hypertext. On the other hand, ending has a crucial function in narratives. As Frank Kermode and Peter Brooks especially have shown, anticipation of the ending is an essential part of following a story[12]. The reader expects the narrative tensions to be solved finally in the end - reading is anticipation of the ending. But then, the ending is not at all that simple a matter even in traditional texts. In the end the narrative tensions (most of them, at least) are solved, the reader learns things she hasn't known before during the reading - as a consequence the reader, in her mind, returns to the story and inserts her newly discovered facts to their proper places, and thus, reconstructs or changes her understanding of events in the course of the story. Of Douglas' arguments for the ending in Afternoon the second and third are apparently Brooksian - established conventions governing the reading of narratives seems to be valid in this context too. But they are not enough alone; an additional, hypertextual factor is needed (like the lack of a default link). This raises some questions. If the solving of narrative tensions and the hypertextual sign of ending do not coincide, the reader may stop reading, even though there may be a doubt lingering in the back of her mind that something has still been left unread. Or the reader may just go on and on with the reading until she is quite simply too bored to continue with the text that seems to tell nothing new anymore. More problematic is the case where the text does not offer any signs of ending. It may be that readers get accustomed to the notion that the ending is a contractual matter which mainly depends on her own decision. But we are dealing with a fundamental change, if texts no more have natural closure - if there is no end toward which the reading thrives.

Self-reflexive metatextuality

Repetition is an essential aspect of hyperfiction - the reader is destined to meet certain lexias time and time again. This aspect is often explicated in metafictional comments ("You've had this dream before, you know"). It is quite common to see similar passages, reflecting the working of that particular text:

This whole electronic circus, this literary pin-ball machine, is nothing less than wish fulfilment and fantasies of domination… […] No, the whole thing stinks, its all a fraud: the illusion of choice wherein you control the options, the so-called yielding textures of words… (Afternoon, "Dialectic")

Werther loves complications -- she says -- he sees all stories as intertwined (Afternoon, "Steadfast")

This works as a comment upon Afternoon itself - all the lexias are interconnected - but with this particular text the comment is nearly redundant, so apparently everything in Afternoon is intertwined.

I'm not sure that I have a story. And, if I do, I'm not sure that everything isn't my story, or that, whatever is my story, is anything more than pieces of other's stories. (Afternoon, "me*")

I kept wanting to put her into some story of my own making. I kept wanting to change the facts, not just the way things happened, but in what order. (Afternoon, "Air")

References to other texts may be interpreted as hints towards models which might be employed in the reading of this particular text too. For example, in Victory Garden there are references to Don Quijote, Tristram Shandy, William Burroughs, Jorge Luis Borges, Thomas Pynchon etc.

Stuart Moulthrop's web fiction Hegirascope - a kinetic text where the lexias follow each other automatically with a fixed delay - starts by reflecting its own functioning. The first lexia reads:"What if the word would not be still?" Later, in the midst of several intertwined story fragments, the text comments upon Internet contents and practices, and more generally, upon media and new media theory. In relation to Internet it is often discussed how the border between fact and fiction is vanishing, and even the term "faction" has been used to describe this phenomenon - Hegirascope comments this in a highly ironic way by "citing" several articles (dealing with Internet and hypertexts), of which most are obviously fraud, or at least, distorted. As reading instructions, thus, they are rather ambiguous. One of the strands in Hegirascope offers a very radical interpretation of the real nature of Internet - in "Curtis LeMay's Web Workshop" we learn that Internet is a weapon for free market capitalism in a fight against communism and because of that it is everybody's duty to design proper web pages, and use HTML code efficiently."Above all, you must know the codes." Coding and page designing is rhetorically parallelled to warfare - and after all, there is some truth to that: Internet was built upon the decentered computer network of US Ministry of Defense (the ARPANET); "Did you know that Internet was designed to survive thermonuclear assault?" Against this background the reader is like a soldier who is "attacked" by the text.

Newcoming hyperfiction readers usually start reading by using default links, and with these "passive choices" get accustomed to the textual world. The next phase, then, is the associative selecting of anchor words. This phase is usually described with an informative intrest: I want to know more about the thing to which this word/ sentence refers. In all articles dealing with the reading of hypertexts, the problems of this type of navigation are noticed: the links quite simply just do not produce the kind of results readers are looking for. "[V]irtually all of her students had given up trying to find verbal cues after a few nodes…"[13]

The first time I read Afternoon, I clicked my mouse haphazardly on any old word, and quickly grew disoriented. Realising I was lost, I began to carefully choose which words to click, but usually couldn't understand the connection between the word I had chosen and the node to which it led me. I never worked out what was going on, who was narrating what and which names belonged to whom. After an hour or so of frustration I gave the whole thing up. (Walker 1999)

…the synaptic associations of Michael Joyce's brain makes one feel somewhat lost 'in the author's funhouse', prey to associative whims beyond one's control,… (Klastrup 1997)

Hyperfiction in most cases raises a computer gamelike attitude towards reading. The functioning of the text turns to a challenge which the reader has to solve, and it easily happens that finding out the deep structure of the text and its functioning principles become the main objective for the reading, instead of an interest in the fictional world. The text turns into a riddle which has to be answered. This kind of reading I'll call 'metareading', or, following Lisbeth Klastrup, 'intentional reading'. In metareading the text poses as a challenge for reader, but at the same time she knows that the real "opponent" here is the author. Even though in the beginning of the reading hypertext seems to offer a new kind of freedom or power to the reader, still, after a shift to metareading she starts to realise that she herself is "subject to programming", that in hypertext authorial control is even stronger than in traditional texts. On the other hand, the easy manipulation of hypertextual structure and the consequential great number of possible combinations necessarily weaken authorial control - the 'intentional fallacy' of new criticism gets new concreteness in hypertextual context. Michael Joyce, obviously, has well understood both dimensions to the situation, and expressed this in a condensed way:"… and the real interaction, if that is possible, is in pursuit of texture. There we match minds." Intellectual challenge and an element of competition originate, drawing from these examples, both from the act reading itself, and through the metatextual instructions.

Jim Rosenberg (1996b) describes hypertextual activity as follows:"Readers discover structure through activities provided by the hypertext." This closely resembles the phenomenon Stuart Moulthrop describes in one of his articles (1991) - according to him students reading hypertext fiction for the first time, intuitively discovered the spatial structure behind the text. Even though I mainly agree with these claims, I still would like to take a closer look at what "discovering the structure" may actually mean. Discovering can mean two different things - the readers may discover that there is a spatial structure behind the surface text, or, they may discover the form of that structure. It is a totally different thing to discover that the lexias are arranged to a certain networked structure, and that one can navigate through that network in several alternative ways, than it is to map out, for example, the following structures[14]:

When we scrutinise the reader as a "discoverer" or "creator" of various structures, we can use Jim Rosenberg's classification of hypertextual activity[15]. He classifies reader's activities to three levels related to actemes, episodes, and, sessions. The actemes, at the lowest level, are various simple actions like following a link or reading a lexia (Rosenberg, however, states that it might be possible to divide the reading of a leaxia to even smaller units). Several actemes together form an episode:"An episode is simply whatever group of actemes cohere in the reader's mind as a tangible entity." From the demand of coherence and tangibility it follows that not just any group of actemes ("reading history") automatically forms an episode - an episode is an interpretational unit, and some of the actemes may not belong to any episode. Session is quite a straightforward concept, a continuous reading experience, which ends with the termination of the reading program. As an analytical tool it is much more vague (Rosenberg explicates this himself) - the terminating of reading may be caused by random causes totally unrelated to the text itself (in which case the reading is probably continued after a while). On the other hand, terminating the reading may be caused by the feeling that the reader has reached a kind of full picture of the work, or even a saturation point (which is the closest alternative to 'the end' in traditional texts). Possible actemes are preprogrammed in the text, and thus they form for the reading a basis independent of the reader; the reader naturally chooses which actemes she actualises and in which order (but there may be reprogrammed restrictions to the order as well).

Episode is already more clearly dependent on the reader's interpretations. The author may include in the text signs indicating certain actemes (George P. Landow has discussed this topic under "the rhetorics of hypertext"[16]), but finally the episodes are produced by the reader. Narrative structure is closely related to the construction of episodes:

Indeed, the whole concept that a sequence of hypertext activities works together as a single story fragment may be one of the ways by which the reader constructs a concept of episode in the first place.[17]

Essays describing the reading of hyperfictions back up this notion - it is apparent that it is just the thrive towards a coherent story which governs the reconstruction of hypertextual structure. From the reader's viewpoint, then, hypertextual syntax is dominated by narrative syntax. This is partly caused by the strong role of established conventions - hypertexts are read according to ways learned by reading traditional texts. But on the other hand, the hyperfictions themselves direct the reading this way.

When talking about the choosing of links and the choice of one's own reading order, we have to be careful - the reader may choose one of the existing links, indeed, but what is this choice grounded on and to what extent does it really offer freedom in "reading order"? The situation is paradoxical in that the choice of links is based on associative thinking, but at the same time it requires cognitive distancing from the textual world. The reader has to reflect on what she wants to read next, but ultimately her choices are all mere guesses: if I click on that word, I'll probably get text related to that and that to read. Referring to several essays about reading hyperfiction we can state that it is just this feature of hyperfiction which is highly frustrating for readers: the associations of the reader and the author do not meet. This can naturally be used as an intentional writing strategy: the author may attach a link to a totally misleading anchor word to create a shocking or estranging effect.

In his article "Reading from the Map: Metaphor and Metonymy in Hypertext Fiction" Stuart Moulthrop has described how novice hyperfiction readers discovered the spatial structure behind the hypertext, even though the structure was not presented as a map. Instead of the metonymy based procedure they measured their reading in spatial terms with regard to that structure, and defined the relations between the lexias in spatial terms. This kind of activity does not, however, necessarily help in the problem of intentional navigation at all, since the categorical difference between narrative and hypertextual syntax makes it impossible to infer the narrative structure directly from the hypertextual structure[18].

Since hypertexts are computer programs, they can be subjected to one special kind of "resistant reading": hacking (or cracking). Espen Aarseth told in a discussion how he exported all the lexias of Afternoon to one text file, and then read them through as a traditional, even though highly fragmented, narrative[19]. I have tried that myself, and the experience to some extent resembled reading Virginia Woolfian modernist narration. This, too, is one way to learn what is inside hypertext.

But we can go even further - in that same discussion Nancy Kaplan told how one of her students had also "opened" a hypertext, but then she had put it together again, changing the link structure according to the modification dates found in each lexia: she had added new links so that the text could be read in the order in which the lexias were included in the text! This may seem like almost a criminal abuse of the text (or at least as cheating in the mind matching game proposed by Joyce), but after all, it is just what all hyperfiction readers are encouraged to do: to take author's position and reconstruct the text as they wish. The student had studied how the text functioned and then taught it new ways to function.

[1] See Genette 1987.

[2] From the leaflet accompanying Victory Garden.

[3] Aarseth 1997, 1; Sukenick (1972) ”The New Tradition”, reprinted in Sukenick 1985.

[4] Following the default link should not be, however, too straightforwardly equated with turning the page, because it may take the reader to a lexia already read, and also, with the so-called ”conditional links” following a certain link may have different outcomes at different times.

[5] Afternoon is not, strictly speaking, static – the use of conditional links means that some of links are not effective at all times.

[6] See, for example, Douglas 1992; Klastrup 1997; Walker 1999.

[7] Markku Eskelinen (1998b; 1999), especially, has written about the differences of chosen and caused changes.

[8] Deena Larsen uses link titles in an original way in her Samplers, in which the titles of links leading from each lexia together, read consecutively, form a poem. In this case the paratext of link titles functions as a parallel text for the main text, not as a means to structure the main text (or only in a very indirect way).

[9] It isn’t necessarily to farfetched to see here a connection to Jean-Francois Lyotard’s notion of the postmodern as a state preceding modern (1989).

[10] Brooks 1984.

[11] See especially "'How Do I Stop This Thing?': Closure and Indeterminacy in Interactive Narratives" (1994).

[12] Kermode 1968; Brooks 1984.

[13] Moulthrop 1991, 128.

[14] Illustrations are taken from Georg Stuart Joyce 1999.

[15] Rosenberg 1996b.

[16] Landow 1992, 56-57.

[17] Rosenberg 1996b, 9.

[18] See G. S. Joyce 1999.

[19] "The Limits of Cyber Culture - Discussion on Cyber Culture" (with Espen Aarseth, Stuart Moulthrop, Nancy Kaplan, Markku Eskelinen, and Raine Koskimaa, in Parnasso 3:1999 [in Finnish]).