[A] project like this is always open-ended. This is the open end.

-Califia

M. D. Coverley (the pen name for Marjorie Luesebrink) has written several relatively small scale web fictions (Endless Suburbs, Life in the Chocolate Mountains, Fibonacci’s Daughter etc.), poetry (RainFrames), parts of various web collaborations (”Elys, The Lacemaker” from The Book of Hours of Madame de Lafayette) - and the heavily multimedial hypernovel Califia (forthcoming). Luesebrink has also been an active participant in the ongoing discussions about the possibilities of digital and networked writing. Her paper in the Ninth ACM Conference on Hypertext and Hypermedia, ”The Moment in Hypertext: A Brief Lexicon of Time”, was an important opening for the discussion of temporality in hypertext[1].

M. D. Coverley’s Califia is a manifold story about seeking a lost treasure somewhere in California mountains (Califia being the name for that treasure). It is a story of three families in five generations – needless to say, the families are complicately intertwined. At one level, Califia tells about three friends, Augusta Summerland, Kaye Beveridge and Calvin, who are all interested in the gold treasure known as a family myth both in Summerland’s and Beveridge’s families. The stories of four previous generations - of a treasure gained, hidden, found, hidden again, and eventually lost; of romances, financial deals and betrayals; of crimes - themselves are as much of interest as the treasure proper. The surface level consists of four journeys that Augusta, Kaye and Calvin take in order to explore that history.

In addition to the surface level narrative there is a wealth of other materials, historical narratives told in chronological order, myths and legends related to the stories, and diverse documents from newspaper clippings to receipts, to deeds, to journal entries, to maps, etc. The surface level quickly turns to a frame story for the unfolding historical narratives (or a narrative, since it all connects to a more or less coherent, despite spotty history). This as an eternal treasure hunting, in which the reader is invited to participate. The reader may find her own trail through the wealth of information and stories gathered in one form or another – but the story also escapes the boundaries of fiction, to the reality, as much as there is to talk about reality in California (Baudrillard had quite a lot to say about that); true to the spirit of historiographic metafiction, there is so much documentary and quasi-documentary materials included that the reader is tempted to go to the Los Angeles Public Library, as recommended in the text, and look for more information from the newspapers and other documents held there. It is also said, in the preface to the third part of Califia, that some of the documents described there were sent to Augusta, Kaye and Calvin, by readers interested in the whereabouts of the treasure. Also, in the end the reader is urged to submit her own experiences in the treasure seeking to Kaye, Augusta and Calvin.

At one level Califia is a quest and a mystery – it also has its share of romance. Augusta Summerland’s father dies and soon after, a Wind Power Company offers to buy a worthless piece of land her father had owned. Just when Augusta is ready to sign a contract, she meets Kaye Beveridge, who begs her not to. She introduces herself and quite soon gets Augusta convinced (or if not convinced, at least interested) that the piece of land has something to do with a gold treasure known in both Summerland and Beveridge families. Augusta’s father had believed in the treasure, and had tried to locate it, even though he had not committed the whole of his life to this task, as many others had. Augusta has not given too much thought for the gold before, but now Kaye gets her interested in the stories. Augusta’s neighbour, Calvin, is also drawn into the quest. Calvin has known Augusta’s family quite well (and knew something about the existence of a possible treasure) – but the connection between Calvin and Kaye is very vague – but it is Kaye, after all, who invites Calvin to join them; he is more than happy do so.

They will take several trips, mainly all three together, to the Paradise Home where Augusta’s mother is being taken care for her Alzheimer’s Disease, to meet the Wind Power representatives, to meet Augusta’s aunt Rosalind (whose whereabouts she learns only after her father’s death), and to the Los Angeles Harbour. During these trips, through discussions with various people they meet, a wealth of stories about their ancestors, and of Califia, is revealed – maybe the biggest piece of news, told by Aunt Rosalind, is that Calvin’s (who has been raised in foster families) real name is Calvino Lugo; his real parents were Tibby Lugo and Nellie Clare Beveridge, which makes him the second cousin of Kaye, and also, as integral a part in the Califia story as Augusta and Kaye are. Between the trips, Augusta, Kaye and Calvin consult the documents Augusta’s father left behind; and Kaye consults the spirits of people already dead...

Alongside Augusta’s chronological narrative there are Kaye’s mythologies and legends, as well as various documentary materials as archived by Calvin, for the reader to choose. These may be read in any order – there are paths through each of the sections (Augusta’s path, Kaye’s path, Calvin’s path), but there are numerous text links between the paths, and, additionally, there are several navigational devices with which the materials can be read (making a digression to some sub-plot; consulting some maps, looking through collected contracts and business letters, opening a new window for watching pictures etc.). In Califia, the hypertext structure is not used to create alternative storylines, but as an archive from which different aspects of the main story can be seeked.

Our memories are always in the process of revision. As Kaye is quick to point out, a composite version of the same event is as close as we might come to truth. Even so, the contour of reality is as elusive as the Terrestrial Paradise.

(”To the Reader, Part III)

The materials do belong to three different levels. These are the present time (the textual actual world), the historical time (as recounted in stories, and recorded in documents), and, the mythical time (the time of astrology and Indian mythology). The three main character’s focusing each on one these levels produces, though, somewhat differing alternatives:

Dear Fellow Prospector:

You may find the rhythm of the story and the cadence of the steps enough. Or you may wish to understand the structure of our project. Because it is three-dimensional, and because it is evolving, Augusta, Kaye, and I see the outline differently… (Topological Maps)

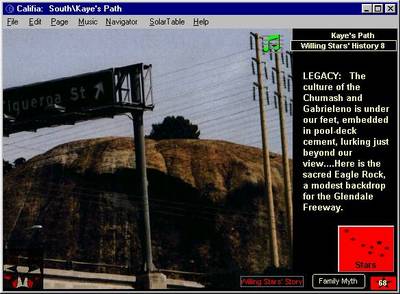

A Screen from Califia

Time and space are two fundamental categories with which we structure the world around us. When spatiality has been extensively discussed in theory and to some extent exploited in practice, it seems odd that temporal issues have been in a sidetrack in the hypertext discussion so far. Because of that we should appreciate Marjorie Luesebrink's presentation in the Hypertext 98 conference about time in hyperfiction. She makes a basic distinction between "Interface time" and "Cognitive time", the former describing the real time activities when reading hyperfiction, the latter describing the time in the fictional text. Each of these categories is further divided into three different modes[2]:

Interface time: mechanical (time spent waiting the program to load etc.), reading (the actual time spent reading the text), interactive (the time spent in interaction with the text - navigation etc.)

Cognitive: real (time of the narration), narrative (time of the narrated, historical time), mythic (the cyclical time of mythologies)

The category of interface time is good as such, and as simple as they seem, these distinctions are necessary and useful. Cognitive time is also a good concept, although I may be giving it a somewhat different meaning than Luesebrink does in her definition. As real time I understand the time of narration, or, the time of the fictional actual world (thus, real time in the fictive world), narrative time is the time of the narrated (fictional history). Mythic time is a concept which works as a leak between ontological boundaries - it is something shared between the actual world and the worlds of fiction, a zone that is not possible to attribute to each of them alone[3]. The numerous references to actual history and actual historical figures (like the actress Bette Davis) in Califia serve to give the text an authentic, documentary feeling – these references can be explained, depending of the theoretical framework, either as referring to the reality outside the fictional sphere, or as referring to fictional objects (historical figures being ”fictionalized” in the text). Mythology, on the other hand, is something not real (in the positivistic sense), it could be compared to abstract categories like mathematical truths; simply, it is not realistic, or fictional, but mythical, and thus exceeding the limits of the fictional world[4].

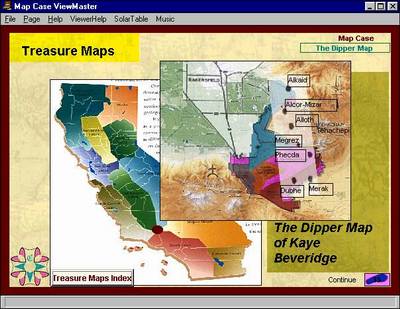

In Califia, then, the real time and the historical time are clearly separeted, whereas the mythical time is always present (see figure below). Real time is open, in a constant process of becoming, historical time is linear, but mythic time is cyclical. This is closely related to all the cyclical phenomena in nature, especially to celestial movements. Star charts – and especially the Big Dipper, or, Ursa Major – play a central role in the efforts to locate the treasure.

A Screen from Califia

Historical time plays the role of the adversary here; it corroses memory, and ruins the landmarks:”The past is fractured and changed and forgotten” (Ernie’s Skull). Mythical time offers the eternal, although enigmatic, directions. In Califia, the time and space chronotope plays a crucial role. All the three temporal levels are present simultaneously, inscribed in the geological and cultural landscape. (see figures above and below)

The category of cognitive time is not specific to hypertext fiction – we can detect the three levels of cognitive time in most fictions. Hypertext, however, and especially hypermedia, seem to suit exceptionally well to presenting mythic time. Through hyperlinks and the hypertextual structure the elements of mythic time can be distributed all over the work; mythic time in a very concrete way permeates the whole of the story of Califia.

A Screen from Califia

Spatiality has been one of the central topics in discussions about hypertexts, but spatial presentation has been in a very limited use in actual hypertext novels. Works like Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl (1995), and Deena Larsen’s Samplers. Nine Vicious Little Hypertexts (1997) do use the spatial map as a site of signification, but in a very schematic way. The possibilities hinted at in Patchwork Girl and Samplers, as well as some features borrowed from computer games, are used in a highly original way in Califia. In Califia there are several ways for navigation: there are star charts, geological maps, timelines etc., all of which structure the text in their own ways. Each of the three main characters are also focalizers for different kinds of approaches to the story/stories, and thus offer different ways to approach the totality of the materials in Califia (Augusta focussing on the chronological order of real time events, Calvin on the arranging of historical materials, and Kaye on the mythological and ancient stories).

The text is furnished with a wealth of images - both pictures and symbolic images which often function simultaneously as illustrations and navigating devices. There is the basic Windows menu bar at the top of the screen, but otherwise the screen is reserved for the content material, which serves also the functions of navigation. Instead of giving a cognitive map of the hypertextual structure, the reader is confonted with geographical maps (often juxtaposed with star charts and treasure maps), which situate the historical and real time events spatially. Or, pictures showing the locations give a local spatiality for them.

This is a very different approach to the spatialization of hypertext as employed in the ”classical hypertext”: instead of relying solely on the spatial aspect of the hypertextual structure, the fictional world is represented as a kind of proto-virtual reality which depicts the hypertextual structure and sub-structures in a naturalized way. This is a good example of the integration of navigation devices into the (hyper)fictional world.

Califia presents us an interactive environment into which the reader can - as with many computer games not using datahelmets and other VR rigs - get him/herself immersed. A good case for a simple comparison is the Broderbund game Myst by Rand and Robyn Miller. In Myst the reader/player can enter the closed world of an island and wander around there, solving numerous problems and fulfilling different tasks. It is as close to the immersive virtual reality experience as it is possible to get without VR rigs. At the same time, however, it has a strong textual element: there are several (partly decayed) books and note slips on the island, which are crucial for the problem solving. But these texts in Myst have another, possibly even more important function: they provide a narrative for the otherwise narrativeless world. The passages in the books are related to different instruments on the island, and in some way they can be said to be hypertextually linked to each other (although the links are not immediate or even obvious); thus, in a polemical vein one could argue that Myst is a hypertext narrative with a very elaborate 3D reader interface...

Put side by side, Califia and Myst clearly show us the difference between hyperfiction and virtual reality: even though the text fragments have an important role in Myst, they are still functioning as one subcategory of effects in that game, and no conclusion can be drawn that text would somehow be necessary in all virtual realities aiming at delivering a narrative[5]. In Califia, on the other hand, everything is language, even though in many instances symbolic language. In Jay David Bolter's terms, everything in Califia is simultaneously meant to be looked through (creating fictional world) and looked at (functioning as a metatextual device), while in VR everything is meant to be looked through[6].

Language has a special capacity for creating worlds - most often this peculiar power of language has been attributed to its indeterminatedness or openness or even vagueness: it evokes a world but leaves it open for the human imagination to complete the proper way. Illustrations, dramatizations and filmatizations of texts always encounter criticism that they tie the receivers' imagination to a prefab model, thus loosing much of the representational power of the original text. One of the central techniques in Califia, to avoid restricting the imagination this way, is its use of symbolic language - from astrology and indian mythology to geographical maps etc. - which provide illustrations that are powerful as pictures, but because of their symbolic nature do not have the restrictive effective sole illustrations would have. Because of this advantage, it is not surprising to notice that also Samplers is based on symbolic (drawn from Indian mytology) representation - as is Adrianne Wortzel's web fiction Electronic Chronicles. Maps are of course one of the most obvious choices for navigating devices, mainly because they are, naturally, made for that purpose in the first hand, but also because they are so easily motivated from the fictional world. Califia, though, makes the solution much more interesting in juxtaposing several maps, and then, motivating the whole hypertextual structure through the limitless variations of juxtaposing these maps.

The juxtaposing of several different, and even incompatible, spaces produces a heterotopic space, as Michel Foucault has termed it in his article ”Of Other Spaces”[7]. A typical heterotopia is a cathedral, where sacred and profane spaces are juxtaposed. According to Foucault, the sacred spaces are quickly vanishing from our culture – because of that, we badly need new ways to experience the immersion in the sacred. I have argued elsewhere that the virtual spaces of cyberpunk science fiction, alongside other functions, work as heterotopic sites, where the sacred finds a realm for a return (think about the voodoo deities in the Matrix of William Gibson’s Neuromancer, or the mystic qualities of The Other Plane in Vernor Vinge’s ”Tue Names”, and the virtual realities in Pat Cadigan’s Synners)[8]. The hypertextual, virtual space of Califia the project, works in the same way, bringing the mythological principles to the same level with the other means of structuring the stories and all the data related to them (and true enough, at one point Kaye does mention the similarity between the structure of Califia and that of Kabbalah). In this it echoes the feelings of JackRabbit Jack, one of the previous seekers:

He wanted to pretect the fragments of meaning that kept slipping away from him. Create a bastion against a future that would hold no promise of magic. (Fish Camp Factfinding)

The other spaces (as Foucault calls them), are also spaces for the Other.

A Screen from Califia (notice the Big Dipper pattern, on the right, coinciding with important mining sites)

Augusta, arguably the protagonist of Califia, narrates the quest in chronological order. This way a general understanding of the Califia history of three families is formed, when the three main persons combine their knowledge of family stories and myths, and integrate information they learn from other persons to that knowledge. While following ”Augusta’s Path” through the text, this is the picture the reader gets – a very general and spotty overview of main characters and events through 150 years and five generations. Augusta’s mother's eventual death, as well as Kaye’s and Calvin’s relationship growing intimate, are recounted in the chronological story.

Calvin’s role in the quest is to keep all the information in order. He arranges the documents Augusta’s father left behind in an archive; he provides them (and the reader too) with a map case, including everything from route maps to maps concerning different geological features of California landscape (fault lines, land slides, earth quake sites etc.); there is photo album etc. And it is Calvin who types in the story written by Augusta on computer. Califia – the work we are reading – is assumedly the electronic document Calvin has built for them to help keep the mass of documents and information in order. This way we readers are in a sense put to an equal position with the fictional characters, as users of the very same archival program they are using.

All the documents in the archives (theoretically, in all the existing archives holding documents in some way relevant to the history of the last two hundred years in California; in practice, all the documents held in Calvin’s archive) help us to understand the stories better, help us to fill in the gaps in the stories told in the Summerland and Beveridge families. As such, in themselves, these documents are only of limited interest; only when we know something about the events they are related to, do they really start making sense to us.

As for documents in the study, they tell the story in the way ancient history reveals itself – fragmented and motive-free. A narrative of indirection. (JackRabbitt Jack 3)

This is the basic situation when we are dealing with attempts to understand, or interpret, all kinds of phenomena: there must be some kind of pre-understanding on which the larger picture is based, and after that, there is circular movement between the general understanding and details. Each new bit of information, its significance, is first, provisionally, interpreted from the viewpoint of the whole – but each bit of information carries with it also the potential to change the whole picture, and thus to change the previous interpretations of other information.

Rosalind seems to be rather good at arranging narratives to hide secrets. So expert, perhaps, that she has buried whole episodes in cold storage, in packages without names. Secret-keeping is one way of coping with realities […]

”That part of the story exists in different versions in my mind,” she says slowly. ”One version is what I believed at the time and continued to consider as the official family account. Another has all the later revelations, the elements that fill in the spaces, answering questions we didn’t want to ask.” (North Point 4)

The family myths and legends the three characters share – with each other, and, through Augusta’s chronological story, with the readers – function as the preunderstanding for Califia. The ”docudramas” Calvin and Kaye construct serve as a ”first round” for the circle of interpretation. The docudramas are short stories, depicting certain episodes in the Califia history, centered around one person or another. They are assumedly based on the known facts of those person’s lives and filled in with guess work by Kaye and Calvin – the stories imagined in such a way that they fit in with both the big picture and the given details. These mininarratives, in their turn, help us to get a clearer understanding of the whole etc.

The new findings along the way mostly just help us to fill in some gaps in the stories, or direct us to make some minor adjustments to the big picture. There are a few bigger revelations, though, one of them being Aunt Rosalind’s story about Calvin’s, or, Calvino’s, childhood. We learn, first, that Calvin is really Calvino Lugo, which is quite significant in itself, since the Lugos play almost as big a role in the Califia history as the Summerlands and Beveridges. But additionally, we learn that his mother was Nelly Clare Beveridge, which fills in a big gap in both Nelly Clare’s and Tibby Lugo’s stories – before Aunt Rosalind’s story Nelly Clare just disappeared in 1939; now we know that she ended up in the La Liebre with Tibby, and lived there at least long enough to give birth to Calvin.

This kind of hermeneutic activity, and especially its explicit thematisation in the story, is common to all mysteries. What is different about Califia is its openendedness – or better yet – its non-closure. There is no real anwer in the ending – it may be that Augusta and friends have located the real place of the treasure, but there have been several predecessors who also have believed the same way, only to be let down time after time. To prove that they finally have found the right place would require a massive excavation in the mountains – an effort possibly too expensive and risky for them to ever go on with. The ”answer”, or, definite ending for the quest, is not sought at all; what is more important is the process itself, knowledge of the place and its inhabitants gained during the search. Califia, then, turns more to a metaphysical quest than a conventional mystery. While metaphysical quests, almost by definition, tend to be universal in their nature, there is in Califia, however, a very strong sense of place – it is firmly grounded in the geography and history of California. While the eternal quest as such is universal, this particular quest for Califia could not take place anywhere else but in California – as is said somewhere in the text: ”The place matters”.

The circular movement is mirrored also in the narrative structure of Califia. The story is told in four parts, each recording one round trip returning to the starting point, Augusta’s house. In the transitory phases between the trips, there is reflection, interpretation, and conclusions, before a new round trip. The four parts are titled according to the general direction of the trip: ”South: The Comets in the Yard”), ”North: Night of the Bear”, ”East: Wind, Sand, and Stars”, and finally, ”West: The Journey Out”. The West, and the Pacific Ocean offer a possibility to step out of the endless cycle, a step necessarily metaphysical in nature – as wonderfully illustrated by Violet’s (Augusta’s recently died mother) spirit walking to the Pacific surf. In another form, there is the possibility to exit from the fictional world. For those, who are not yet taking that step, the cycle continues.

This openendedness can be seen in connection to the proto-virtual reality-like quality of Califia. It is at least as much a landscape to wander in and out, as a narrative with a beginning and an end. You can always take another route through the landscape, looking how it looks like at different times, from different angles:

Granted we did not find the riches of which we had been told, we found a place in which to search for them. (Footprints 4)

Hypertext, as Ted Nelson defined it, means ”non-sequential writing – text that branches and allows choices to the reader, best read at an interactive screen”.[9] And cybertexts,

in their turn, are texts which function in some way. What do we mean by ”interpretation” when we are dealing with texts which are constantly in the middle of a process – either subject to readers’ choices, or to programming, or to both simultaneously? And is it possible at all to interpret something in which you have to be involved (if not immersed) as an active participant in the meaning production? Or is it the case that the distance necessary for interpretation kills the participatory process and thus, in a sense, denies the object of the interpetation totally?

Tentatively we may assume that, taking into consideration the almost infinite variety in the field of hyper and cybertextuality, there is variation also what comes to the possibilities of interpretative activity. I will now compare Califia with Stuart Moulthrop’s Victory Garden, from the viewpoint of interpretation.

Califia and Victory Garden exemplify two very different ways to use hypertextual structure in narrative fiction. Califia can be described, on a very basic level, as an archive. The archive is collected around one master story, the historical Califia saga – all the other narratives (including the real time narrative of Augusta) are just sub-stories in that saga. The archive is very open, it can be approached and used in many ways, and in many orders. The way one uses the archive does not, however, alter the master story. The hypertextual structure does, in the spirit of Nelson’s definition, allow choices to the reader, it serves also as a platform for the multimedial contents of the archive. All this does not, however, in any radical way affect the interpretational activity. The way the archive is structured and the devices to use it, are more a matter of usability than of interpretation. During reading there is the movement from details to the big picture and back, but there is also the possibility to step back from the immersion and scrutinize the work in its entirety. As mentioned earlier, the exit point is to some degree only provisional, and the text encourages repeated readings (wanderings in the fictional landscape of Califia) – it is, however, clear that after some point only minor alterations are possible.

There is also the aspect of the fictional world’s expansion or intrusion into the real world – the reader is asked to consult the documents in the Los Angeles Public Library, the reader is asked to contribute her own stories to the Califia crew etc. This way it completes the thematisation of the hermeneutic interpretation at work throughout Califia. The reader enters the fictional world with knowledge of real world – this knowledge then functions as the first framework through which the text is naturalized. When the reading proceeds, the autonomous laws of the fictional world presented are foregrounded, and the interpretative activity concerns mainly the relation of details and story fragments to the whole story. When the saturation point is reached and the reader exits the story world, it is once again compared to the real world. One more circle in the hermeneutic activity, and the fictional world is integrated into the experiences of the reader, and it becomes a part of the reader's world. It has always the potential to affect the reader’s worldview, and thus condition further experiences. In its extreme form, it could be argued that the hermeneutical interpretation is the affect the work has on the reader’s understanding of the world.

With Victory Garden the situation is different. It cannot be satisfactorily seen as an archive. It is, rather, a machine, or a system, which produces different stories. These different stories do not contribute to any master story. Furthermore, in many cases they are totally incompatible with each other. With a text machine like this the hermeneutic interpretation described above, is not as easily employed. The details and story fragments cannot be integrated to any whole, or interpreted from the viewpoint of some big picture, because there is no big picture[10]. There are only alternative stories, and once you exit the story world, take the necessarily distance to interpret the work, you can never know what the next event would have been, had you chosen to read just a little further. In this case there are two possibilities for interpretation. The first option is to treat that version of the work you have read as the sole subject of your interpretation. It may appear more or less fragmentary, but once you have decided this is all there is, it is always possible to construct interpretational frames which explain the fragmentary nature, and possible contradictions, of the narrative. But there are some inherent problems with this kind of an approach. The biggest of them is the question what we do with that kind of interpretation – after all, it is possible that no other reader ever read the work the same way. There will be as many works as there are readers. Thus, the differences in interpretations are not primarily products of different interpretive conventions, but of a more fundamental order: they are interpretations of different works. This is, naturally, not to deny the value or legitimity of such an approach; we just have to make clear that in this case we are dealing with experiences that gain much of their aesthetic force through their (quasi)unique nature.[11]

The other possibility is to try and understand how the text machine works, what the rules and limits for the story production are. Once the mechanism is explained, it serves as a general model of which any single reading is just one possible actualization. Activity like this can be compared to the practice of poetics, in which a set of common properties is ”distilled” from a body of texts (the oeuvre of certain author, genre, period etc.) Instead of ”The Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics”, we could, then, scrutinize the problems of Victory Garden’s poetics. This means acknowledging the generative nature of hypertexts in the interpretational activity. By means of the metalevel interpretation we can construct a common background to which any individual reading is compared. That way it helps us to overcome the solipsism described above. We can also give a meaning to the mechanism; a part of the interpretation must be explaining why this particular mechanism is used and what is its statement – and even further, how it is functioning together with the materials subjected to it.

We now have the two opposite kinds of hypertexts – Califia, which is perfectly well suited to hermeneutical interpretation, and Victory Garden which is best suited to poetics. These are both hypertexts which are clearly static in nature. With dynamic texts evolving in time, the situation is different again. They are best seen as any historical events which must always be arbitrarily limited to comprehensible units, which then are interpreted in relation to all relevant circumstances, and keeping in mind that they are only local interpretations of certain phases of ongoing processes. And here we return to hermeneutics.

[1] Luesebrink 1998.

[2] Luesebrink 1998, 107-111.

[3] This comes close to Thomas G. Pavel's (1986) ideas of different ontological spheres and their changing borders

[4] See Harshaw 1984.

[5] Sören Pold has written a paper about the ”scripted space” in games like Myst, arguing that the each of the screens in Myst are ”scripted” to contain fragments of stories (Pold 1998).

[6] Bolter 1996.

[7] Foucault 1986.

[8] Koskimaa 1997b; see also McClure (1995) about spirituality in postmodernist fiction, and Davis (1993).

[9] Nelson 1993, 0/2.

[10] With Victory Garden, there may, after all, be a possibility for a big picture. I am exaggerating here a bit, for the sake of argument (it is not hard to imagine a hypertext narrative a bit larger and even more complex than Victory Garden).

[11] Quasi-unique, since any particular reading of a hypertext can be repeated in exactly the same order. In this case, a part of the work has gained an independent status, it has become a work of its own.