”It was a fine idea this two-world doctrine, but the seal would not hold." (Victory Garden, ”Worlds Collide”)

Fictional ontology is about the ontological domains of fictional texts, "fictional worlds", and the relations between them. The innovation central for the development of fictional ontology is the notion, grounded in possible worlds semantics, that a fictive text is not a "world", but rather it is a fictional universe, a structure of multiple alternate worlds[1].

According to the conventions of realistic fiction, each fictional universe has a centre, "reality of the text", which will be called the textual actual world. Orbiting this centre, there is a variable number of other worlds. These are, for example, dreams, counterfactuals or embedded narratives (which can be descriptions of pictures, plays, etc.). These worlds are called textual alternative possible worlds. Then we have to consider one more world to exist, the textual referential world, of which the textual actual world is a representation. The textual referential world can be more or less similar to our own actual world, but theoretically they must always be separated.[2]

The three kinds of worlds, the textual actual world, the textual alternative possible worlds and the textual referential world, together constitute fictional universe, the domain of fictional ontology. The fictional ontology is closely related to the narrative discourse - there are in print fiction, then, two parallel circuits: the textual universe and the hierarchical structure of narration. In hypertext fiction there is still the additional hypertextual structure. These three circuits affect each other, but should not be confused[3]. As a point of departure we can take the preliminary notion that the levels of narrative embedding always constitute an ontological domain, but the border between fictional worlds does not necessarily imply a change of narrative level. The complications hypertextual structure causes for ontology are more complex, and will be discussed in detail below.

The fictional universe can be made complex either discursively or through the multilayered ontology of the referential world (which duality roughly corresponds to the difference between postmodernist and science fiction/fantasy). The hypertextual structure can be used to strengthen both of these strategies.

In the following I will look at Philip K. Dick’s science fiction novel Ubik (1969) from the perspective of fictional ontology – I have chosen this particular text because it nicely illustrates a narrative device which strongly foregrounds fictional ontology, and which plays a central role in hyperfiction poetics. I call this device ontolepsis, the ”leaking” of ontological boundaries, narrative metalepsis being a special case of ontolepsis.

In the world of Ubik there are characters, who can see to the future. However, they can not manipulate the future events (a situation very easily causing paradoxes). Narratively speaking we are dealing with prolepses, where the order of plot is manipulated at the level of narration. In mainstream fiction prolepses are explained by the abilities of omnipotent narrator, or they are presented as more or less accurate guesses. For science fiction it is typical to concretize this kind of discursive structure or naturalize it with some special cadget or ability (foreseeing etc.)

Manipulation of the past events is an essentially different phenomenon and it cannot be compared to the narratological analepses (flash-backs) as such. A more accurate equivalent for it in the field of narratology is unreliable narration. In unreliable narration an event is first represented in a certain way, but later it is revealed not to have happened that way (or at least made suspect). So here we are not dealing (usually) with changing the past, but with representations of it. And the later representation, seen as more valid, causes us to overcross the former version. However, the crossed-over event still remains a part of the reading experience, only its status in totality of the text is changed[4]. In Ubik, there occurs a phenomenon of "world under erasure", too, but it is not as interesting as manipulation of the past, from the point of view of fictional ontology.

In Ubik, a young girl called Pat can manipulate past events, and as it seems, consequently the present as well. As readers we most probably will not find it satisfying enough to consider the consequences of Pat's action only as a case of unreliable narration. For that reason I will present a reading grounded on the possible worlds model, which is capable to more concretely describe the science fictional world of Ubik.

Pat reveals her special ability when she tells how her telepath father (able to see the future) saw the girl to crash a valuable vase the next week. Little Pat was punished immediately for a deed she did a week later. It was hard for the girl to realise the limitations of her father’s ability, when he could do nothing to change the things he knew to happen. Many days she thought about it, and finally decided to concentrate only on thinking the vase and imagining that it had not crashed after all. And then, one morning, she saw the vase in one piece in its place, without no one except herself remembering it ever was crashed.

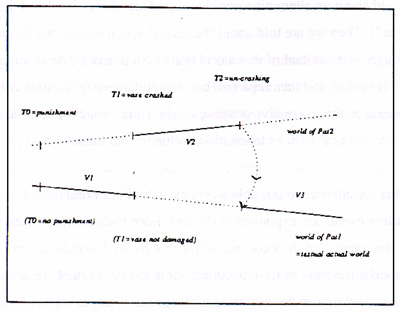

At the state V1 of the textual actual world the vase is complete. The event T1 (=the crashing of the vase) starts the state V2, which ends up with the event T2 (=the un-crashing of the vase by thinking). After that follows the state V3, where the vase is undamaged again. This happens at the level of the narrative discourse. If we are to reconstruct the world told (the events as they happened in the textual referential world), we can see that the state V3 comes right after the state V1, without the event T1 (or better, the event T1=the vase does not crash). The state V2, and events T1 and T2 related to it, never occur in the textual actual world. Seen from the textual actual world the state V2 is a part of an alternative possible world (what had happened if the vase had crashed), which exists only in Pat's mind.

The reader easily gets the feeling that the vase first crashes and then is undamaged again. However, it is not like that, because in the textual actual world the vase never crashes. This confusion is caused by the existence of two characters called "Pat". First there is the Pat1 in the textual actual world, who is narrating the vase story. Second, there is the Pat2 in the alternative possible world. Even if these two characters are the 'same', they have to be separated, because they exist at different ontological levels and have (at least) one difference: Pat1 has not broken the vase, and Pat2 has.

Narratologically we are speaking of (embedded) dual focalization. The vase story narrated by Pat1 is focalized (partially) through Pat2. And that is why readers do believe the vase is both broken and being saved. At the start we are told about an alternative possible world and this is focalized through an inhabitant of that world (Pat2). Then we are told about the textual actual world, and this is both narrated and focalised through an inhabitant of this world (Pat1). So this is a case of simultaneity, not of diachrony. The vase is not broken and then repaired, but it simultaneously remains unbroken in the textual actual world and breaks in the alternative possible world. (It is, though, plausible to think an occurrence "the vase is nearly broken" to have taken place in the textual actual world.)

Although we can decide that the alternative possible world exists in Pat's mind only, it is still interesting to notice how these events are explained in the text. Both Pat's ability and the foreseeing of the telepaths are based on the premise of the existence of infinite parallel worlds. Every event in history not only could have happened differently or have occurred not at all, but each of the possibilities always have actualized. The situation can be visualised by Jorge Luis Borges’ famous metaphor of forking paths. Every event is a fork leading to different paths, and each of them in their turn fork to new paths etc. The textual actual world is just one path, which is the consequence of all the events that happened, and decisions that were made, in its history. There is, however, an infinite number of other worlds around it, and they all differ more or less from it.[5]

The telepaths can see forward along these paths, and, what is most important, they can distinguish the paths which are to actualise in the future of their world. Pat, on the other hand, can influence the selecting of the paths in the past.

The contradiction connected to the vase story above, the feeling of something at the same time to have and have not happened, follows from inhabitants of two worlds somehow fusing into a one character. Narrator-Pat seems to include both Pat1 and Pat2. Narrator-Pat has a memory of experiencing the alternative possible world as actual. This can be explained by saying that the experience is not real. Pat has imagined or dreamed an alternative world, and has dreamed it so vividly she has mistakenly believed it to be real. This interpretation is based on the concept of unreliable narration. The possible worlds model, which is referred to in the text, argues, however, that the alternative world exists independently of Pat's mind. The conflict can only be explained by some kind of a mysterious connection between these worlds. And behind this connection there can be nothing else but Pat's special ability.

In the parallel worlds model there is an infinity of other worlds alongside ours, but no one in the actual world can perceive these other worlds. Pat's speciality lies in her ability to move from one possible world to another. In this model she cannot manipulate the course of the past events, which is theoretically impossible; behind this model lies the idea of every possibility having actualized, at every moment. Events which are contradictory occur in different worlds - we can see Pat's ability this way: she can experience more than one world as actual (that is, exist in many worlds) and furthermore, she can cause this experience to other people, too.

Finally, strictly speaking Pat's speciality lies here: she can move parts of one world to another, alternative world. These parts may be, for example, certain individuals' experiences. In a normal situation, both world V1 and world V2 exist, simultaneously and independently. In these worlds exist two persons, Pat1 and Pat2, who are each other’s counterpersons, that is, their essential properties are the same, although their accidental properties may vary[6]. There should not be any kind of relationship between these two persons, except that they can naturally both imagine the world where their counterparts would exist. In the latter case the counterperson, however, is always a non-actualised possibility.

In a normal situation, then, in each one world there can exist only one Pat as actual, and the other (and of course, the whole infinity of others) is always non-actual. But this specific person, Pat, can jump from one world to another. This happening she merges with Pat belonging to the other world on all their common properties, but she brings with her some differences at the same time. So there are the minds of two persons contained in Pat the narrator. These two persons are almost identical, only memories of some two weeks differing slightly. The two minds are not equal, however, because only one of them contains the experience of moving, through a voluntary act, into another mind. Thus, Pat1 experiences continuous existence, while Pat2 feels an experience of distortion, which is caused by being submerged to be just a part of Pat1. There is no clue of how Pat1 has felt this fusion of minds, because narration of the event is focalised through Pat2 only. Despite this complex play with fictional ontology and multiple selves, it should be noted that behind it lies a discursive structure after all - that is, presenting two different focaliser-characters as one.

Narratological concepts can handle this case. There are two diegetic levels and focalizers connected to them. Depending on the interpretation it is, or is not, a case of narrative metalepsis. If the interpreter thinks Pat's ability to be only her own imagination and the vase-story a dream, then there is no metalepsis, but unreliable narration: narrating Pat (Pat1) has not experienced the feelings of narrated Pat (Pat2) as actual, even if she herself thinks so. Pat2 is in this case a person existing only in the dreamworld (hypodiegetic level) of Pat1, to which dreamperson, having lost her sense of reality, she strongly identifies herself with.

However, we can think of two different worlds, not in hierarchical relation (absolutely speaking, the narration necessarily posits the other one as actual and so as primary) and the two Pats exist each in their own worlds. This kind of situation is a bit difficult for Gérard Genette's narratological vocabulary. Using it we necessarily end up with the first interpretation: the two worlds are two embedded narrative levels. If we are to believe the idea presented in the text, both worlds existing indepently and simultaneously, then they cannot be hierarchical, embedded systems.

This can be seen as an example of dual ontology, as presented by Thomas G. Pavel[7]. One diegetic level is ontologically divided into numerous levels (potentially infinite but in this case into two only). Now we can make an adjustment to Genette's model. In addition to the diegetic levels we have to take into consideration the textual-ontological borders

To sum up, the diegetic levels always create a possible world, but the text as a semantic unit can create further possible worlds without creating new diegetic levels. Because we are dealing with semantic content here, the structures, both narrative and ontological, are always independent of interpretation. There are formal relations between the two circuits, but these relations can be examined only after some initial interpretation has been established.

In Robert Coover’s short story "Quenby and Ola, Swede and Carl" (1969) there are several possible plots. Using the Russian formalists' terminology, from the sjuzet of the story, several different fabulae can be constructed. In practice the reader must choose one of these possibilities at a time. So in this case the alternative possible worlds are only potential; the gaps of the sjuzet leave space for different interpretations. Explicitly self-conscious gaps foreground the possibility of different parallel interpretations of the "real" fabula. This way it produces the same kind of situation as we encountered in Dick's novel. Many parallel alternative possible worlds seem to leak in to each other. When Dick presents us alternative chains of events, Coover's story concentrates on the branching points of the events, leaving them purposefully open, that is, the personality of the acting subject (also the focaliser) is never revealed. The gaps quite simply make the reader to think "what did really happen"? This pondering can produce (at least for some readers) several different possible worlds. As Brian McHale has formulated it: ”Carl, a businessman on a fishing holiday, either sleeps with one of his fishing guide's women or he does not; if he sleeps with one of them, it is either Swede's wife Quenby or his daughter Ola; whichever one he sleeps with (if he actually does sleep with one of them), Swede either finds out about it or he does not. All of these possibilities are realized in Coover's text.”[8] – but the thing of utmost importance here is that none of these possibilities can be read as totally ”clean” from the influence of others. The possibilities are theoretical constructions – in practice they are fused, merged, infected by each other.

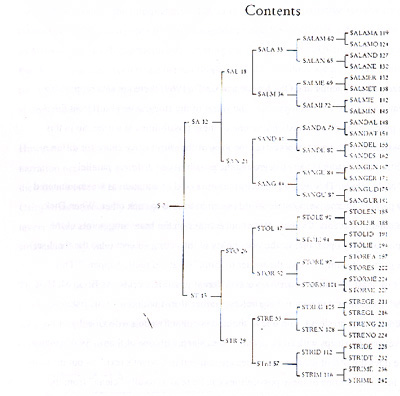

One more print fiction example should be discussed here. Svend Åge Madsen’s ”novel” Dage med Diam (Days with Diam) is not as well known as Coover’s or Borges’ stories, but in its highly interesting, strictly hierarchical structure it deserves attention. Days with Diam is a paradigmatic case of the fiction of forking paths. The narrative starts with a chapter titled ”S” – after that the reader can make a choice between two chapters, she can go on reading chapter ”SA” or ”ST” – from ”SA” there are the options of ”SAL” and ”SAN”, from ”ST” the options ”STO” and ”STR” and so on and so forth, each chapter having two possible successors.

The Contents Page from Days with Diam by Svend Åge Madsen

All in all, there are thirty-two different stories, each being told in six chapters. If the reader chooses to read the book in this suggested order, then it can be seen as a strictly hierarchical and symmetrical hypertext. The points of departure are very clear – the whole text is like a treatise on the contingency of life, on how every decision bears consequences for the future. In the first chapter the protagonist is dozing off in his cottage pondering if he should drive to the railway station to meet his lover (her train will stop for twelve minutes at the nearby station). In chapter ”SA” he goes to the station and is taken by surprise, since the woman, Diam, tells him she has arranged things so that she can spend three days with him. After that there are sixteen different variations of how those three days are spent. In chapter ”ST” the protagonist (Sandme – an anagram of Madsen) does not bother to drive to the station for the twelve minutes.

If the reader reads the ”ST” section of the book first, she probably won’t pay too much attention to the question if Sandme should go to the station or not – after all, it is only a question of the twelve minutes the train stays at the station. But if the reader has read the ”SA” section of the book first, then the situation is totally different. Now the reader cannot but think how sad Sandme’s decision really was – Sandme himself may never know that instead of twelve minutes he actually lost three whole days with Diam. From the point of view of fictional ontology these two worlds should be totally inaccessible to each other – they are alternative possible worlds, and in each, a certain decision shuts the other alternative out for good. In the reading process, however, they are both present, one is infected by the other. This is a form of ontolepsis which is an unavoidable part of hypertext fiction. In this case the logic behind is so explicit that the reader should not have great difficulties dealing with incompatible scenes – each action causing the different alternatives is so clearly marked.

There are other kinds of ontolepses in Dias with Diam, too, which are closer to the Ubik example above. Here are two scenes from two closing chapters of alternative stories:

In the foyer I meet Agla coming out of the toilet. She looks as though she’s been crying. She turns towards me, and I have a feeling that she needs to talk to me.

I hesitate, and smile as encouragingly as I can. Then I continue into the main room […] (124, SALAMO)

… a girl issues from the toilet. She seems upset, and looks away so as not to let me see she has been weeping. At that moment the door opens and a man enters. The girl looks at him, waves happily to him and makes to go towards him, but the man only vouchsafes her a quick glance and goes on into the lounge. (130, SALANE)

Taken separately these two scenes have nothing special in them – despite the fact that they resemble each other in many ways. But if these alternative stories are read consecutively, there is more than just a vague resemblance. It is as though the narrator, Sandme, were duplicated in the latter scene. From the previous story (SALAMO) we have learned that it is Sandme who is passing Agla without stopping to talk to her. Now we see the same scene, narrated again by Sandme, but as an outsider. He does not recognise Agla (in this version (SALANE) they have never met), but he does not recognise the man as himself, either. There is nothing in the latter scene itself which would give reason to think of the walking man as Sandme – this is purely a consequence of the ontolepsis between the two story worlds.[9] Naturally this is an intentional trick, the scenes are composed assuming that the reader will notice the curios change in personas. While this kind of trick inevitably leads to confusions and works toward breaking a coherent interpretation, there are balancing factors: personality as an interchangeable role is one of the recurrent themes in the book, and scenes like this only reflect that idea.

Scenes like this – there are too many of them to be counted in Days with Diam – take the ontolepsis into the fictional world, a character from one story is transferred into another story (with a slight variation).[10]

If we take as a starting point the notion of diegesis divided into alternative possible worlds, we can think of the paths in hyperfiction as alternative narratives relative to these possible worlds. The situation, however, is not that simple. Because of the hyperlinks, the reader may read fragments of several paths in an order totally independent of any preordered paths. She may even construct new narratives, unpredicted by the author. One solution, then, might be seeing each possible narrative constructed by the reader as constituting a related fictional world. This is still too simple – the fragments from different paths may not always produce any one coherent narrative – the reader may, and in most cases does, get the feeling that she is reading incompatible fragments from several narratives. In trying to construct a coherent interpretation, there will often be incompatible elements – there is not any master explanation making all parts fit.

I would like to suggest, rather, that for the most part the reader clearly recognises she is reading several narratives simultaneously, intertwined. Some of them may be ordered as plots and sub-plots, or, as different temporal phases of one plot, but there often are contradictory materials, or pieces, that for some reason do not fit in. Hypertext theory has been neglecting this inevitable effect – the theoretical assumption has been that there are several clear-cut narratives in the hypertextual structure. As with Coover’s short story, these narratives, for the reader, (almost) never exist in pure form. Despite the stress on the empowered role of the reader, the actual characteristics of reading hypertext fiction have been pushed aside. With hyperfiction, ontolepsis is so overwhelming, so unavoidable a phenomenon, that it should be taken into consideration more openly.

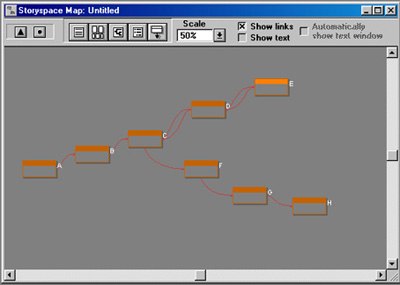

In addition to the general tendency towards ontolepsis in hyperfiction, there are the special cases when the reader has read a certain story path for some time, and then decides to backtrack her way for a couple of lexias, and then choose an alternative link, leading to different consequences than the first choice.

What is the status of the two lexias (D, E) in this reading? Or as Jim Rosenberg has asked, do they belong to an episode or not?[11] I believe they are an essential part of that reading. In a sense they have activated the reader more than some other segments – instead of simply following the default path she has made a conscious decision to go back to a certain point and find an alternative story line. Even if the sequence D-E, seen from the alternative line (C-F-G…), is now sous rature, neglected or discarded, it is still, unavoidably, there. The effect is very near to the one we encounter in self-concious, self-denying postmodernist fiction:”It rained. It did not rain.”

The mechanism of ontolepsis in cases like this differs from that in Dick’s Ubik. While the ontolepsis in Ubik played a role inside the fictional universe, in hypertext narratives the ontolepsis (usually) takes place outside the fictional universe, in the reading activity, in interpretation. But the effect is the same: it is as if parts were transferred between different worlds. Naturally there is no reason why hypertext fiction could not thematise ontolepsis as well. Michael Joyce’s Afternoon and Stuart Moulthrop’s Victory Garden include several such passages. In Victory Garden there is the ”Ring” sequence:

Ring Around

U is once again still always running through that dark field, slipping scrambling through his own footprints on the dry ground. He knows Madden is behind him somewhere but he doesn't dare look. You've had this dream before, you know.

In some versions of the story this scene appears three times with slight variation. To a reader who happens to read only this one part of the cycle, the mention, ”You’ve had this dream before, you know”, is nothing but a remark strenghtening the dream-like atmosphere of the scene. For a reader who has read the two previous phases of the cycle the situation is different – she knows, sure enough, that this has happened before although she may not be so sure that the reason for the repetition is a recurrent dream (there are other possibilities like virtual reality simulation available).

We now have to take a closer look at the relations of the three domains of hypertext fiction:

In hypertext fiction we have to take the possible worlds model described above for granted – instead of simply imagining that this or that event might have happened in several ways resulting in potentially very different consequences, some of events really do happen in more than one way.

Joker

[…]

"Holy shit," Veronica said when she saw who was squeezing out of the little cab.

"Evenin' y'all," Billy Van Saxgutter said, squaring up his string tie and removing his hat. "Does one-a yew ladies happen t'be Perfessor Dor-thea Agnew?"

"Billy Van," Veronica called out to him. "Be cool for shit's sake."

The merry prankster squinted up at her. "Izzit that little Runnin' Bird?"

|

|

|

[leads to:]

What If It Was?

[…]

The cowboy-agitator pulled himself up and traightened his Lone Star belt buckle. "Perfessor Agnew," he told Thea, "me'n the boys here don' exactly approve of yore tryin' t' stomp on Western Civilization an' our Amurkin way've lahf. And Ah do confess we come up here tonight t'make a purty emphatic show of our displeasure. But owin' to the respect Ah have fer our young friend there, Ah'm gonna advise mah associates t' leave peaceably." |

[leads to:] Uh Oh...

Now this was where the real trouble started.

One minute Billy Van Saxgutter was down in the back of the bus having himself a fine old time tearing out handfuls of that leftist-liberal upholstery while working on a fresh can of beer. The next thing he knew he was sitting there trying to keep his pants dry in the face of certain death.

It seems somehow the Rainbow Bus had caught fire. […] |

Depending on the point of view, we may either think about the hypertextual structure as a reflection of that situation, or, as a basis and a presupposition for that variation. This is analogous to the double nature of fictive narration – while we pretend the narration to represent some pre-existing reality (world), it is simultaneously the case that narration actually creates (or, stipulates) that very same reality.

Because of hypertextual structure, there can be several variations in the following categories:

1. which events do take place (story, textual referential world)

2. the order of the events taking place (story, textual referential world)

3. the order in which the events are narrated (plot/narration, textual actual world)

4. the way in which the events are narrated (narration, textual actual world)

In the general communication structure of narrative fiction (”text describes how the narrator tells what the characters perceive”[12]) all the categories above belong to the domain of narrator – thus the reader has an access to some functions usually performed by the narrator, and because of that I have elsewhere suggested that instead of the ”reader as author” phrase, it would be much more accurate to talk about the ”reader as (co)narrator”.

We could say that each change, no matter which category it belongs to, produces a new text. Each scripton is a text of its own, and each reading (scripton) of a certain hypertext is comparable to an individual book (story, novel) – thus we would be dealing with the ontology of fiction (not fictional ontology). This is, however, strongly counter-intuitive[13]. It is more plausible to think about a hypertextual work as one work which represents one fictional universe – in this approach the different scriptons are related to fictional ontology (to the ontological domains inside that fictional universe).

Even though it is the very hypertextual structure which makes the ontological variation possible, the hypertext structure itself does not organize the ontological (or narrative) structure – on the contrary, it is a means of disorganization. If we had no hypertext links, then we simply had a collection of stories. Add some links from one story to another, and you have a hypertext – and you have leaks between the story worlds, stories infected with other stories. Narrative levels and ontological structures are interpretational conventions we use in order to make the text coherent, hypertext is an opposite force undermining that coherence. Conditional links are a tool to locally tame the destructive power of hypertextuality – in that sense I accept Aarseth’s claim that conditional links do not belong to a ”pure” hypertext[14].

Anti-hierarchical, disorganizing hypertextuality undermines the possibility of narrative structuring to some extent. For example, the division between the events as they happened (story/fabula) and the order they are told (plot/sjuzet) is one of the basic elements in narratology. Gérard Genette has constructed the most detailed system to classify all the possible relations between these levels.[15]

When there are several versions of both the fabula and the sjuzet, it may be become extremely difficult, if not impossible, to establish any clear relations anymore. But as Jill Walker’s paper ”Piecing together and tearing apart: finding the story in afternoon” (1999) shows, with hypertexts like Afternoon, phenomena like prolepses (anticipation) and analepses (flashbacks) still can be identified.

Ontolepsis in print fiction is a violation of narrative conventions. In postmodernist fiction it is used as a metafictional device to foreground ontological questions. In science fiction and fantasy it is presented as a feature of the foreign world. In hypertext fiction ontolepsis is an integral, unavoidable part of the representational logic. The great challenge for hypertext authors lies in finding ways to use it as a native part of the writing, and for the readers, to learn not just to tolerate it, but to learn to love it…

[1]This view of fiction is presented both in Ryan (1991) and Dolezel (1988; 1992). The terminology I am using is borrowed mainly from Ryan. The most thorough account of possible worlds theory and fiction is Ronen (1994).

[2]The old mimesis question is lurking here. I find Ryan's use of "mimetic-discourse" quite reasonable. We can speak of mimetic representation between the textual actual world and the textual referential world, without messing with the real world. Thus mimesis is not primarily a question of reference in respect to reality. I find Ryan's (and Dolezel's) way of thinking fiction more accurate than Benjamin Harshaw's "double decker" model, which just does not go far enough (mainly because he is speaking only about realistic fiction). (Ryan 1991, 24-29, Harshaw 1984)

[3]The relation of the textual universe and the narrative discourse is thoroughly discussed in Margolin (1991). However, his main interest lies in the referential status of different utterances and how these utterances create fictional ontology. Margolin's article is important background for this study, but he is not analyzing anomalies of narration typical for postmodernist fiction (and also, for hypertext fiction).

[4] For events "under erasure" as a postmodernist device, see McHale 1987, 99-105.

[5]About parallel worlds theories, see Lewis 1986.

[6]Transworld-identity is thoroughly analyzed in Eco 1979, 229-236.

[7]Pavel 1986, 54-57.

[8] McHale 1987, 107-108.

[9]Michael Joyce refers to a similar phenomenon when writing about Julio Cortazar’s Hopscotch:”…he calls upon us to recall not the subject but, instead the act of our previous readings and invites us to read Hopscotch in a successive, literally programmed iteration. This second reading depends upon our decaying, yet dynamic, memory of the master text.” (Joyce 1995, 138)

[10]I want to thank Lisbeth Klastrup for bringing this wonderful book to my attention.

[11]Acteme is a low-level unit of hypertextual activity - such as following a link, or, reading a lexia. Episode is a group "of actemes [which] cohere in the reader's mind as a tangible entity." (Rosenberg 1996b, 3)

[12]Tammi 1992, 10-11.

[13]Naturally there is a counter-example for the counter-intuitive argument: Milorad Pavic’s novel The Dictionary of Khazars is printed as two books, the female edition and the male edition – these differ from each other only in one paragraph – otherwise the 300+ pages are identical!

[14]Aarseth 1997, 75.

[15]Actually, there is also a third level for Genette, that of narration.