The digital media have produced a whole lot of new kinds of texts. Most of these are only marginally or potentially literary, but there are exceptions, especially the so-called hypernovels. That there are literary hypertexts should not be a surprise, since Ted Nelson, the father of digital hypertext already thought his system as essentially literary: Literary Machines is the title of his most influential book[1].

The number of literary hypertexts is still quite low, but they have succeeded in producing a wealth of theory. George P. Landow, most notably, has been visible in proclaiming the close relation of hypertextual writing to post-structural theory: "hypertext creates an almost embarrassingly literal embodiment of [Derrida's de-centering and Barthes's writerly text]".[2] It has to be admitted that hypertexts are indispensable in concretizing abstract theories like those of deconstruction, but there seem to be some potentially dangerous simplifications behind these comparisons.[3]

The wealth of theoretical writing, in its turn, has produced a jungle of terms and concepts - digital literature, hypertext literature, hyperfiction, hypernovel, hyperbook, interactive literature, topographic writing, nonlinear text, multilinear text, secondary orality etc. Espen Aarseth's recent book, Cybertext. Perspectives on Ergodic Literature (1997), is the first serious attempt to build a comprehensive and systematic theory of the new modes of textuality. Aarseth is not afraid of being polemical in respect to previous theories: differentiation between print/digital texts is a misleading starting point, "interactivity" as a concept is totally useless without further qualifications, cybertexts are not narrative texts, and the omnipresent influence of narratology is a "dystopia". His own approach is to define a new category, that of ergodic literature, which includes both print and digital texts (even though it is obvious that the digital media offers more flexible devices to this use). His other central concept is cybertext - which has been quite widely used for some time already, but to which Aarseth gives the first real definition: "cybertext is a perspective on all forms of textuality (18)". And needless to say, the perspective of cybertext stresses especially the ergodic aspect. This aspect in print texts has usually been seen as an anomaly, and as such, it has stayed under-theorized - considered as mere postmodern(ist) trickery.

In what follows I'll first give a more detailed explanation of the characteristics of ergodic literature, and then I'll take a closer look on some texts often mentioned in connection with hyperfiction - texts which have been dubbed proto-hypertexts - and try to find a) what in each of them is specifically "ergodic", b) how the knowledge of new digital literature affetcs the reception of these texts, that is, is "cybertext" really a new perspective to them, c) how these proto-hypertexts possibly may help us to understand and to produce digital ergodic texts, and finally d) whether ergodic texts necessitate the remodeling of old literary theories, or even the constructing of wholly new ones.

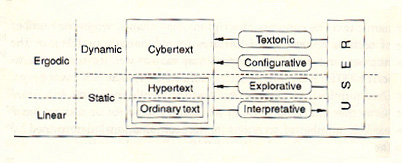

"In ergodic literature, nontrivial effort is required to allow the reader to traverse the text. If ergodic literature is to make sense as a concept, there must also be nonergodic literature, where the effort to traverse the text is trivial, with no extranoematic responsibilities placed on the reader except (for example) eye movement and the periodic or arbitrary turning of pages." (Aarseth 1997, 1-2) In this quotation, the expression "extranoematic" should be understood as something like "other than interpretive" - that is, following the lines and turning the pages are "trivial" efforts, and also, interpretation (generally) is an unavoidable part of all reading. When reading ergodic texts, there is always something else going on in addition to trivial efforts and interpretation. This something else has been classified by Aarseth as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The advantage of Aarseth's classification is the way it condenses in a systematic way the ad hoc classifications of previous theories (it includes, for example, Michael Joyce's very influential distinction between exploratory and constructive hypertexts[4]). "Explorative" in practice is making choices between different possibilities, but since navigation as a term implies a textual network consisting of a mass of opportunities, I would like to add to the Figure 1 "selection" before "explorative" - selection is clearly local and more limited than navigation - as such it is very useful with respect to print proto-hypertext. It's rightful place, then, is at the border between "ordinary text" and "hypertext".

An example: a text divided into two parallel columns, like Samuel R. Delany's "On the Unspeakable" (1993), forces its reader to choose in which order s/he reads it (left column first, right first, or jumping from column to column, a line at a time) - in cases like these it feels exaggerated to speak of "exploration".

The instances of reader's selections gives rise to the question of the linearity of text. Ted Nelson originally defined hypertext as "non-sequential writing -- text that branches and allows choices to the reader"[5]. This definition has been repeated frequently, but is has also been strongly criticized, by stating that the reader's selections finally produce a linear text in any case. George P. Landow's compromising solution has been to speak of "multilinear or multisequential texts"[6]. Landow's term has been widely accepted, so it comes as quite a surprise how Aarseth strictly demands a return to Nelson's original definition and nonlinearity:

"A nonlinear text is an object of verbal communication that is not simply one fixed sequence of letters, words, and sentences but one in which the words or sequence of words may differ from reading to reading because of the shape, conventions, or mechanisms of the text" (41)

"...while he [Nelson] is talking of text and writings (as constructed objects), they are talking of readings and writing (as temporal process)" (44)

Thus stating that "reading is linear" is trivial, but if we focus specifically on (ergodic) texts as objects, we have to admit their nonlinear nature. In addition to this major statement about linearity, Aarseth also proposes a minor adjustment with respect to the nature of reading:"multicursal would be a much more accurate term than multilinear" (44)

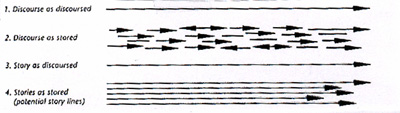

After all, the result is that the reader, when reading a nonlinear text, constructs a linear version of it. This activity has been related to Gerard Genette's story-discourse concept by Gunnar Liestøl, who adds two more levels to the model[7] (see figure). Ergodic text contains bits and pieces of both story elements and discourse elements, and the ergodic activity of the reader constructs the linear discourse as discoursed (the text as actually read)[8].

In the traditional narratological model the actual reader has been cut out of the consideration (as well as the real author), but with ergodic literature there is no discourse before the reader has made it (that is, employed either explorative, configurative, or textonic user function). From this follows the necessity to keep an eye on the actual reader too - at least to some extent. With web fiction, the author has always the option of going back to the text and making changes to it available - this same option may be offered to the readers as well - which, in a sense, makes each web text at least potentially cybertextual. In any case, the communication model for ergodic literature is completed only when the reader makes the feed-back loop complete[9].

With Vladimir Nabokov's Pale Fire (1962) we can detect an obvious hypertextual quality already at the surface level: the text (poem) - commentary structure. This is one of the basic modes of non- or multilinear text. In addition, there are two further texts, "Foreword" and "Index", which multiply the textual network. These four different "statuspheres"[10] appear to be clearly separated - the links between the texts are (almost) invisible. With the hypertext vocabulary we may say that the anchors in Pale Fire are weakly marked. The poem, "Pale Fire", is line-numbered, but there are no other anchors. In commentary the anchors are marked with a line number referring to the poem, and with a quotation explicating the passage commented upon the "Index" is list of two-fold links - the anchor word(s) can usually be found only from the "Commentary", but a line number refers also to a relevant place in the poem.

It is possible to read the book in a totally traditional manner, from the first page to the last, as any other novel - but the difference lies in that before doing this the reader has already had to make a decision - I'll ignore the "Commentary" and the "Index" when reading the poem itself. That decision (or, naturally, the decision to skip between poem and commentary frequently, for example) is an additional, non-trivial effort from the part of the reader - it is, then, an instance of ergodic activity.

What makes things much more complicated is the relation of the contents of the statuspheres to each other. There are dozens of books and articles trying to explicate what it is that actually goes on in this text. One interesting treatise on Pale Fire is Peter Rabinowitz's "Truth in Fiction" (1977), in which he states that the main theme in the book is the relation between two texts, poem and commentary - but because the nature of both of these is to some extent up to the reader to decide, it is in practice impossible to determine what this relation is[11]. Rabinowitz distinguishes four different audience types (relevant for every narrative text) and traces the difficulty in reading Pale Fire to the complex constellation of these audiences in this particular text. In order to be able to make any interpretation of the text, one has either to make a decision to consciously privilege one reading over the others, "or to read the novel several times, making a different choice each time. As in a game, we are free to make several opening moves; what follows will be dependent upon our initial decision. Simply with respect to the questions suggested above, we can generate four novels, all different but all couched, oddly, in the same words."[12]

This quotation has a lot in it. First, there is this idea of reading the book many times in different ways - that is, to exhaust the permutational possibilities, which is one of the main strategies employed when reading hypertext fictions. The difference is that in the case of Pale Fire the possibilities are, after all, more limited.

But even if the combinatorial possibilities in the discourse as discoursed level are strongly limited, there are other linkages in the text as well, and those are not few:

Pale Fire develops (to a degree that is almost absurd) the Nabokovian concern with "correlations" between disparate elements (...). Within the novelistic universe each of the separate levels describes a search for hidden linkages: S keeps seeking for "Some kind of link-and-bobolink, some kind/ Of correlated pattern in the game" on the level of his own life; K[inbote] seeks to establish a relationship between his personal life-history and S[hade]'s poem; and the novel as a whole promotes still another pattern, which is left for the reader to decipher. (Tammi 1985, 206)

Even if this kind of linking may be seen as an essential property of text as such (as Barthes does), the explicit nature of this web of links in Pale Fire makes it a more concrete device. From the ergodic point of view we may think that the main problem for the scholars trying to interpret Pale Fire is the attempt to link everything to everything else - and yes, it seems to be so that everything connects, but a coherent whole is possible only by selecting some parts of the text . And this may be to many an impossible principle. But using Rabinowitz's idea of the four different audiences all being used extensively in Pale Fire, no reader, not even a literary scholar, may hold more than one position at once.

Here we have the main difference between ergodic and narrative texts in a condensed form: narrative text may, at least in principle, be reduced to one voice. "According to K[inbote]'s own estimate, 'it is the commentator who has the last word'(…), and at least in a purely narrative-theoretical sense he is correct", writes Pekka Tammi in his narratological analysis of Pale Fire (1985, 218). Ergodic text is always a collage of (possibly excluding) voices: "This voice is not functionally identical to various types of narrators that we observe in narrative fiction, since the ergodic voice is both more and less than the teller of a tale" (Aarseth 1997, 114). Naturally, if we do look at primarily narrative texts, like Pale Fire, from the cybertextual point of view, it is always possible to undermine the clear-cut hierarchies of narratology, and question the reduction of the text to one (narrative) voice.

The second interesting thing in the quotation above is the idea of text as a game - as chess in this case, naturally. For Aarseth, the cybertext reader is a player in a concrete, not metaphorical, way: "The cybertext reader is a player, a gambler; the cybertext is a game-world or world game; it is possible to explore, get lost, and discover secret paths in these texts, not metaphorically, but through the topological structures of the textual machinery." (4) Even though Pale Fire is not an ergodic text par excellence it is a world game, and there is even a possibility of discovering "secret paths" through the different statuspheres (the "Index" has a large role in this respect).

It should be noted that the elaborate web of links and relations in Pale Fire are not limited by the boundaries of that one novel - already the title opens a huge field of intertextual references to Nabokov's other novels, his autobiography, Shakespeare etc. Thus, in the textual labyrinth of Pale Fire, there is always new secret paths to find.

The third point of interest is "all couched,…, in the same words". This reveals a crucial point: with print fiction the material signifiers - words - are permanent, thus the possibility of multicursality is dependent in the subtle choice of words used. They have to be connectible in various ways and still make sense. Even with the digital hypertexts the author/s are facing this same problem - and the best thing a would-be hyperfiction author could do, would be reading carefully through Pale Fire.

The network of internal relations in Pale Fire works as a kind of metastructure - a pattern that connects: "This meta-structure does not exist in linear fiction which only consists of one linear narrative." (Fauth 1995, 5) And, to make an obvious move, it is quite well suited in respect to Nabokov, for whom there always was the invisible web of connections behind everyday life. I have a very strong sense that Nabokov would not have approved much of what French philosophers (and psychoanalysts!) Deleuze and Guattari have written, but it seems to me that in Pale Fire Nabokov has actualized his artistic ideal in a way that comes close to their concept of a rhizome.

Comparing to Pale Fire, Robert Coover's short story "Quenby and Ola, Swede and Carl" is a more limited and more focused text. It tells several different stories, depending on the reader's interpretation. McHale gives a brief description of the possibilities:"Carl, a businessman on a fishing holiday, either sleeps with one of his fishing guide's women or he does not; if he sleeps with one of them, it is eitjer Swede's wife Quenby or his daughter Ola; whichever one he sleeps with (if he actually does sleep with one of them), Swede either finds out about it or he does not. All these possibilities are realized in Coover's text." (McHale 1987, 107-108)

The story consists of short passages told from an unspecified viewpoint (to be exact, the identity of the focaliser is unspecified). The magic with which the manifold story works is in the unspecified personal references and in the uncertainty of the narrator and focaliser from a passage (lexia) to passage. And finally, the story is cut off at the point where one of the possibilities would have to be chosen as the textual actual world. The first two strategies are exactly same ones that hyperfiction is heavily dependent on, the third, on the other hand, is effective only in closed print fiction. The perfection of the kind found in Coover's story would be required of hyperfiction, only in a much larger scale, if it is expected to behave like linear narratives:"Theoretically, the hyperstructure could be pieced together so elegantly and perfectly as to always produce a satisfying linear story..."[13] Coover's story uses the aesthetics of ergodic literature, but in purely traditional form, that is how it challenges its readers.

In its own way "Quenby and Ola, Swede and Carl" is a perfect "literary machine". It is much sounder than Coover's other experiment in the field, "The Babysitter", which is based on four parallel storylines spiralling around each other and ending in a sentence which contains all the possible endings - even contradictory ones. "The Babysitter" is happening on many levels simultaneously - especially the television has a significant role as an additional ontological level.

The paradox of the situation is that for hypertext Coover's type of multilinearity seems a dead end. It would be easy to rewrite "Quenby and Ola, Swede and Carl" as a hypertext, but this kind of "art in a closed field" cannot be a basis for too many texts. "The Babysitter", after all, with its epistemological and ontological fragmentation - and especially because of the leaks between these fragments - seems to be a much more productive model for hyperfiction.

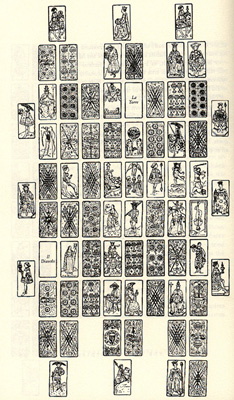

Italo Calvino's The Castle of Crossed Destinies is a story collection written according to a Tarot deck: the cards are assembled in columns and rows which intersect each other, and the stories are based each on one row or one column of cards. The effect, then, is that also the stories intersect each other; they use the same materials, but the meaning of each card depends on the current story. The collection of stories is yet again an example of multilinearity - the Tarot cards serve as building blocks, of which different combinations and different stories have been put together. Without knowing the technique behind the collection, an unwary reader might easily miss the whole interconnectedness of the stories. But it is not just explained, there are also illustrations of the respective Tarot card tables in the book; in this The Castle of Crossed Destinies very much resembles one of the most complex hypertexts yet written, namely Shelley Jackson's Patchwork Girl. In this hypertext (in which passages from Frankenstein are mingled with Jackson's own fiction, quotations from feminist and French philosophers and interpretations of Frankenstein) the cognitive map of the hypertextual structure is in a few places used as a site of signification (especially in a section called "Crazy Quilt"; see figure). Calvino's story collection (as well as the Oulipo poetics in general) should be a useful sample case to people developing programs for computer-generated stories, but it also serves well as one more example of how print fiction can imitate ergodic literature (Calvino's writing procedure, as he describes it in the Epiloque, is a description of pre-digital ergodic text making[14]).

|

|

| "Crazy Quilt" from Shelley Jackson's Patchwork Girl | Tarot Cards from Italo Calvino's The Castle of Crossed Destinies |

Julio Cortazar's Hopscotch (orig. Rayuela) is one of the most famous pre-digital ergodic texts. Hopscotch consists of 155 numbered chapters. "The table of instructions" advices the reader:

In its own way, this book consists of many books, but two books above all.

The first can be read in a normal fashion and it ends with Chapter 56, at the close of which there are three garish little stars which stand for the words The End. Consequently, the reader may ignore what follows with a clean conscience.

The second should be read by beginning with Chapter 73 and then following the sequence indicated at the end of each chapter. In case of confusion or forgetfulness, one need only consult the following list:

73-1-2-116-3-84-71-5-81-74-6-7-8-93-68-9-104-etc.

Each chapter has its number at the top of every right-hand page to facilitate the search.

This "hopscotching" from chapter to chapter, back and forth, is clearly "non-trivial extranoematic" reading activity in Aarseth's terms. Also, the two/many books notion right in the beginning is an explicit indication of the multicursality of this text. And even more, Hopscotch is already almost over the edge, nearer to hypertext than ordinary text. In this case it seems quite relevant to speak of "navigation" instead of mere "decision" - there is even this navigation device and all.

Hopscotch is much larger than Coover's or Calvino's stories, it is a book of more than 500 pages - thus it is clear it cannot be based on the same kind of seamless structure. Its textual elements (lexias) are much more diverse in nature - both contentwise (narrative pieces, poems, newspaper articles, quotations etc.) and lengthwise (ranging from a few lines to more than thirty pages). The main character is an Argentinian writer, who lives in Paris, but travels back to his native Buenos Aires. It is the jumping forth and back between the two continents that is echoed in the "hopscotch" structure of the book, the other materials being kind of interludes and escapes to intellectual-aesthetic spheres in the midst of the everyday circus (Oliveira works temporarily both in an asylum, and in a circus).

Raymond Federman's book Take It Or Leave It (1976; TIOLI) is a print equivalent of "reluctant narrative", "antinarrative", or "sabotaged narrative" as Aarseth describes Michael Joyce's hypernovel Afternoon (1987). I'll now list and briefly describe various strategies employed by Federman to achieve this end.

The intrusion of a member of "real" audience into the fictive world of the narrator. This is in no way a unique strategy, but the explicitness is significant here. This may been seen as an anticipation of the forthcoming hypertextual fictions, in which the reader becomes the author, as is often claimed.[15] With a highly ironic twist in TIOLI, it is not, after all, the virginal fictive world which is raped by the intruding "interactive reader", but the audience member himself, who ends up being sodomized by the narrator! This is a good reminder of the dangers of ergodic (participatory) modes of textuality.

The text as a pre-text. TIOLI is supposedly a tale of a trip through America, from Fort Bragg, North Carolina to San Fransisco. The trip is even shown in a map-like illustration in the first pages of the book. There are also very realistic scenes which anticipate events in San Francisco, after the narrator finally gets there. But it so happens that due to unlucky circumstances the narrator never gets any further than to Camp Drum in Upper New York. When the book ends, the narrator is lying in a hospital about a dozen of bones cracked after a misfortunate parachute jump, and the whole trip is cancelled. Compare this to the following statement by Aarseth: "when you read from a cybertext, you are constantly reminded of inaccessible strategies and paths not taken, voices not heard." (3) It is like TIOLI actually were just one reading of a larger text - and this reading happens to lead to a dead end. But there are those "echoes" from the parts not actualized, and the effect is very much like the one a reader is very likely to experience when reading hypertext fiction.[16]

Questionnaire [to be sent back to the publisher]. Somewhere in the middle of TIOLI the reader is confronted with a questionnaire (complete with a cut off -line). There are twelve yes/no -questions plus a couple of additional ones ("P.S. Do you think all books should have such a QUESTIONNAIRE?"); the questions are mostly about the book itself ("Have you liked the recitation? Is it clear that the JOURNEY is a metaphor for something else?" etc.). Nobody up to date has actually mailed a filled questionnaire to the publisher, so obviously it has been understood as a literary joke - but the world has changed since the publication date (1976). In 1997 Finnish author Markku Eskelinen published a novel with a questionnaire (not totally unlike the one in TIOLI), with which the readers could ask different kinds of changes/additions/deletions/variations etc. to be made to the original novel (all new passages naturally cost something). The new passages are then added to the author's Internet homepage twice a year, so that the book continues its life in the Net.[17] In a world like this, who knows if Federman (after the new printing of TIOLI in 1997) might receive filled questionnaires from active readers?

Indeterminate order of chapters. The sections of the book can be read in any order:"all sections in this tale are interchangeable therefore page numbers being useless they have been removed at the discretion of the author". Because many of the sections are reminiscences and only weakly connected to the unfolding of the main story (the trip), they could actually be read in any place. Paradoxically, though, the omission of page numbers is rather an obstacle than a help in possible unordered reading - it would be easier to locate beginnings and ends of sections if the pages were numbered (this is a perfect manifestation of the phenomenon mentioned by Aarseth: "The book form [paginated], then, is intrinsically neither linear nor nonlinear but, more precisely, random access" (46). In practice, readers very rarely employ the "random access" method with fiction. Alasdair Gray seems to accept this, when he writes in his novel Lanark (in which the chapters are not printed in the proper order: first comes Book Three, then Prologue, Book One, Interlude, Book Two, Book Four, and Epilogue): "I want Lanark to be read in one order but eventually thought of in another." (483) He counts on his readers to read from start to finish despite the numbering of chapters, but uses the table of contents to provoke a mental alternative to that order.

Secondary orality. When Walter J. Ong wrote his book about the technologizing of the word, he actually wrote about word processing, but I think that his ideas are even more accurate in relation to the electronic writing of today - e-mailing for example, and especially hypertext fiction. The mode of writing produced by such hypertext programs as StorySpace - with which most of hypernovels are written - is essentially episodic, and repetition works as a central narrative mechanism.

Despite the resemblance with primary oral literature there are also significant differences: whereas with primary orality the episodic structure was a necessity - poor Homer had to rely on his memory alone - with secondary orality the episodic structure and repetition are just a couple out of many possible artistic devices. As Ong writes:

We like sequence in verbal reports to parallel exactly what we experience or can arrange to experience. When today narrative abandons or distorts this parallelism, as in Robbe-Grillet's Marienbad or Julio Cortazar's Rayuela, the effect is clearly self-conscious: one is aware of the absence of the normally expected parallelism.

Thus:

deplotted stories of the electronic age are not episodic narratives. They are impressionistic and imagistic variations on the plotted stories that preceded them. Narrative plot now permanently bears the mark of writing and typography.

TIOLI is subtitled: an exaggerated second-hand tale to be read aloud either standing or sitting. The motivation for the fragmented structure is the essentially oral nature of this narration. It is not just oral narration in front of an audience, but second-hand (secondary) oral literature, since the story is originally told by another person "leaning against the wind at the edge of a precipice". This figure with which Federman describes the situation of a fiction teller, or just of human existence, is particularly apt with hyperfiction authors and narrators. The links between different text blocks (or lexias, as they are usually called[18]) are frequently described as breakdowns or abysses, and some have even argued that the function of a link is not to connect, but to disconnect.[19] Thus, the hyperfiction narrator is continuously "on the edge of a precipice". With oral literature, as well as with ergodic literature, the dialog with the audience always threatens the unfolding of the story - these audience-induced digressions (though naturally only simulated ones in TIOLI) are the main motivation for the digressive structure of the book[20].

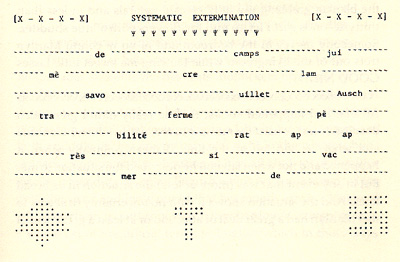

Excessive use of typography - concrete prose. The performative aspect is quite obvious: TIOLI imitates oral telling (as shown above), BUT at the same time it makes use of extreme typographic devices, exclusively tied to writing, even to typewriting. Federman's first book, Double or Nothing, with its even wilder typography has been been described as "a collection of 240 concrete poems"; Brian McHale has termed TIOLI as an example of "concrete prose". He writes about the passage shown in the figure below: "It is the gaps that convey the meaning here, in a way that the shattered words juif, cremation, lampshade, Auschwitz, responsabilite, and so on, could never have done had they been completed and integrated into some syntactical continuity¼ This shaped passage, it seems to me, serves to prove (if proof were needed) that concrete prose can be a good deal more than just a trivial joke.(186-187)

The narrator of TIOLI presents a kind of manifesto in the first pages, where he writes how "Leaning against the winds over a precipice syntax integrates itself to the constraints of the paper", there is a battle of "syntax upon syntax against syntax", all this resulting in "the unpredictable shape of typography!". It is interesting to keep this in mind when reading Jim Rosenberg's article about the philosophy of hypertextual writing:

Therefore, words, sentences, paragraphs (and of course the punctuation) and their position on the page and in the book must be rethought and rewritten so that new ways (multiple and simultaneous ways) of reading these can be created... The space itself in which writing takes place must be transformed... It is within this transformed topography of writing, from this new paginal syntax rather than grammatical syntax that the reader will discover his freedom in relation to the process of reading a book, in relation to language.[21]

The notation of Rosenberg's own "diagram poems" suggests an alternative to the dominant disjunctive hypertext structure: hypertext built up from scratch using very fine grained word elements - hypertext used to carry the infrastructure of language itself, e.g. syntax. One may speak here about hypertext as a medium of thought: rather than hypertext serving as an association structure for thoughts which are not themself hypertextual, an individual thought itself is "entirely" hypertext.[22]

I think that what Federman has done, especially in Double or nothing and TIOLI, the excessive use typography as a part of the signifying structure, is the most radical, and most important hypertextual quality of his work. In the case of Federman, the writing is not just reproduction of thoughts, but the medium for thoughts.

At the time when hypertext narratives were mere futuristic ideas, it was frequently imagined how, in cases where a fictional character was told to read a newspaper article, it would be possible for the reader to see that article too (or even the whole paper); or if the character read a novel, the reader would have access to that novel too etc. In other words, all the materials the characters were faced with, could be reached in their entirety by the reader too. This particular aspect of hyperfiction hasn't actualized, there are no hypertexts written according to this aesthetics - but when one reads Gilbert Sorrentino's print novel Mulligan Stew, that idea seems oddly relevant. With sections titled "Lamont's scrapbook", "Lamont's notebook", and "Halpins journal" almost everything what the narrator(s) see (or better, read, since these materials are almost purely written texts) is recounted in the book.

I'll take a closer look at one article written about Sorrentino's novel, and try to show how its way to examine this exceptional piece of fiction is problematically limited, but how it simultaneously, though only implicitly and (obviously) unintentionally, refers to some important aspects of the book, as well as of postmodernist metafiction in general.

Charles May treats Mulligan Stew as an exemplary case of postmodernist metafiction, and aims to explicate the ways how it challenges the readers' attempts to reconstruct a fictional reference world. He first complains about the dominant role of secondary materials:

The layered documents take over, impinging upon the narrative audience's appreciation and acceptance of that primary fictional world. The total novel is only marginally (and ineffectually) concerned with that particular world, which never seduces the narrative audience into involvement.(243)

It is unclear if May uses the term narrative audience here in the same way as Rabinowitz (as fictional narrator's fictional audience, that is, roughly the same as narratology's narratee). I believe, though, that he uses it simply to mean "the audience of the narrative", that is, the real readers. In that case, his claim is not only exaggerated but false. Although there most obviously are other readers feeling like May, I'm sure I am not the only one feeling just the opposite: the various documents are so powerful as vehicles of the narrative just because they frequently manage to seduce the reader to get immersed in one more new topic. These ever new topics, though, are not the real beef for May[23]:

At the very worst the reader is left with a vision of a purely virtual fictional world, one that includes no genuine irrefutable truths, but only indications of what might have happened. Because the "actual" center in such a world is empty, since the text presents only possibilities, how can the authorial audience identify a modal center as reference world?...This fictional world is sketchily constructed out of these miscellaneous documents that provide no cohesive narrative voice. (250-252)

May's article is a prime example of "traditional criticism", which has problems to accomodate ergodic literature to its theoretical framework. Even though Mulligan Stew is only marginally ergodic (or, possibly, only simulates ergodic functioning), it still presents serious problems. On the other hand, May, rightly I think, locates his own problems in the empowered role of the reader in the interpretation process (it is this "expanded" interpretation required from readers that may be said to be the ergodic quality in Mulligan Stew):

But with postmodern metafiction the realization of the signified falls more and more exclusively on the reader as the interpreter of signs and is recognized by that reader as increasingly inappropriate […] Text-external knowledge still demands integration within a reference world, but only the most fragile structure of truth can be envisioned to accomodate those elements. (256)

In the last sentence of the quotation above May actually has got a hold of the thing, but his quest for the fictional truth blocks his vision. In the best case, a "most fragile structure" can be detected but that requires a lot of work from the part of the reader, and, what May does not explicate, the construction of metalevel above the materials connected - a structure that connects, would hypertext theorists say. But despite this fragile structure, postmodern metafictional texts, according to May, undermine the "coherence quest as the main structuring principle for reference world construction." And here is the main weakness in May's article: he fails to notice how the coherence can be satisfactorily found at the metalevel, while the reference world is left in a state of logical confusion.

From the cybertext perspective the case of Mulligan Stew looks quite different - although it has to be stated that Mulligan Stew can be appreciated even from a non-cybertext perspective, as McHale does in his Postmodernist Fiction. Where May blames the book for ontological instability, it is this precise quality which makes it interesting for McHale, for whom ontological concerns are the dominant mode of postmodernist fiction. Parts of Mulligan Stew do arouse the ontological questions intentionally, but here, as well as with all the books discussed in this paper, there are parts in which the ontological ambiguities are better understood as consequences of other functions.

Mulligan Stew is metafiction par excellence. It depicts an author, Anthony Lamont, struggling to write his murder mystery. One of the reasons for incoherencies bothering May is that the reader is given access to the (fictional) author's drafts, which time and time again are rewritten. Thus, the reader gets glimpses of alternative narrative possibilities, of which only some can be actualized in the finished novel. The book is very much heterotopic to use Aarseth's term - it cannot be reduced to a single narrative without destroying the essence of the book.[24]

In discussions about hypertext narratives it is frequently stated how the reader becomes an author when getting the control over the narrative flow. As mentioned above, in principle I am against this view. The question is much more about something similar to the case with Mulligan Stew: the hypertext carries in its structure the process of its own development - that was the exact idea of Vannevar Bush when he first imagined Memex, and Michael Joyce's approach when writing about constructive hypertext is very much the same. So even though the reader will not become the author s/he will be allowed, and in fact required, to perform functions normally assigned to the narrator. Thus, the reader may decide at some point that s/he isn't interested in reading a particular strand of a hypertext narrative any longer, backtracks his/her reading path and at some point chooses an alternative strand. Jim Rosenberg has taken this example up, and has asked if we should consider the aborted sequence as a part of the episode or not. For the fact is, the reader cannot make the deed undone, s/he has irrecoverably read something from an alternative story strand and this passage remains in his/her memory during the consequent reading. And naturally, the example closely resembles the one in Mulligan Stew, where the reader reads first a scene, and then learns it was only a draft possibly discarded later and irrelevant for consequent action.

This kind of leaking between separated domains in text described here (an instance of effect I have dubbed ontolepsis elsewhere) is an unseparable part of ergodic literature. If we are to accept the claim that socially constructed reality is increasingly getting fragmented (for example, through the ever expanding role of various media in the social construction of reality[25]), then it seems unavoidable that the growing number of borders (interfaces, if you wish) between separated domains expands the instances of "leaks" between these domains. Thus, ergodic texts may be seen as reflecting the postmodern reality in their structure. It is not just so that ergodic texts teach their readers to handle multiple incompatible possibilities simultaneously, but also that the readers are already familiar with that situation, and thus ready to appreciate ergodic texts. All in all, looking from the present situation, Mulligan Stew still looks like a horn-o'-plenty of narrative mastery, but not that "strange" anymore.

The main teaching we can draw from the analysis above is the processual nature of all reading, which is dramatically strenghtened with ergodic literature. There have been numerous efforts to build theories (narrative and other) incorporating the temporal process of reading. The problem has been in the the real reader has been neglected, and tried to get rid of by various means. Stanley Fish's reading of his own reading of Variorum is skilful, and productive, but very limited in its scope. Wolfgang Iser's broad approach to reading as a process somehow collapses to confusing tangle of various agents (text, narrative, implied reader) not including the real reader[26]. Reader as filler of gaps, however, is still the most theorized aspect of the reading process. It is not enough, however, at least when dealing with ergodic texts:

[there are] the differences in teleological orientation - the different ways in which the reader is invited to "complete" a text - and the texts' various self-manipulating devices are what the concept of cybertext is about. Until these practices are identified and examined, a significant part of the question of interpretation must go unanswered. (20)

The new constructions consists of "interactive dynamic" elements, a fact that renders traditional semiotic models and terminology, which were developed for objects that are mostly static, useless in their present, unmodified form. (26)

The incompleteness of narrative theory is most salient with digital ergodic texts, but I have tried to show how many print narratives already seriously challenge the current models. This should be no surprise, keeping in mind the origin of narratology in the static models of structural semiotics.

Aarseth's most radical statement seems, however, somewhat exaggerated: "thus hypertext is not a reconfiguration of narrative but offers an alternative to it, as I try to demonstrate through the concept of ergodics" (85), and "narration can take place without narrative (as defined by narratologists)" (94). The mistake of seeing ergodic texts like hypertext as narratives is due to the general mistake:"argument seems to rest on an unwritten assumption: that fiction and narrative are the same"[27] (84-85). I largely agree with Aarseth - ergodic texts may contain narrative components, but as a whole, they cannot be understood purely on terms of narratology. On the other hand, the empowered processuality of ergodic texts helps us to see the intrinsic processual quality of narrative texts too. Especially the cases of limit texts like the ones discussed here, which, to me at least, are primarily narrative texts, and only secondarily ergodic ones, the right solution cannot be abandoning narratology altogether, but remodeling it to accept the empowered role of the real reader. Thus, the experiences with ergodic literature help us to see the ergodic aspects as legitimate elements in written fiction, not just mere violations of correct forms.

The authors of digital ergodic literature, on their turn, have quite a lot to gain from their non-digital predecessors. To put it shortly: literary achievements like the ones discussed here show how far the limits of static print page can be pushed. In their multifarious forms they set the starting point, from which the dynamic digital texts should start their exploration even further[28]. And artistically, they set the standard, which should not be abandoned just because of the new technical innovations.

[1] Nelson 1980. The father of the idea of hypertext - though still working in the pre-digital era, is commonly seen as Vannevar Bush with his Memex (see Bush 1945).

[2] Landow 1992, 34.

[3] It is interesting, though, to notice that the birth of first hypertext system, Nelson's Xanadu, coincides quite neatly with the publication of Derrida's De la Grammatologie (around the mid-60s) - something in the air?

[4] Joyce 1995, 41-42; Aarseth's figure also demonstrates the problem of the term interactive: interaction may happen in many ways, interpretation being one of these. Thus, all reading really is interactive, but also, there are differences between interactions. Most of the functions described by reception theorists, like Wolfgang Iser's "filling of gaps", belongs to the domain of interpretation.

[5] Nelson 1993, 0/2.

[6] Landow 1992, 4.

[7] Liestøl 1995, 97.

[8] I have discussed this topic more throroughly in my article "Visual structuring of hypertext narratives", ebr 6 (1997). Following Markku Eskelinen's suggestion, we could reformulate Liestøl's terminology after Aarseth's cybertext theory: 1. scriptonic discourse, 2. textonic discourse, 3. scriptonic story, 4. textonic story.

[9] With dynamic cybertexts, where the author may rewrite the text at any time, the actual author, too, has to be taken into consideration.

[10] The term comes from Landow & Delany (1995, 11).

[11] Brian McHale seems to agree with Rabinowitz: "Pale Fire, in other words, is a text of absolute epistemological uncertainty: we know that something is happening here but we don't know what it is, as Bob Dylan said of Mister Jones." (1987, 18)

[12] Rabinowitz 1977, 140.

[13] Fauth 1995, 6.

[14] Not exactly "pre-digital" - but from the time before computers were accessible to the large audience - this is an important note since Calvino was clearly well informed about the development in the field of cybernetics. See for example "Cybernetics and ghosts" - a lecture dating back to 1967.

[15] This situation in TIOLI is in accordance with my previous article, where I argued against the idea of "the reader as author", suggesting, as a better alternative, "the reader as co-narrator" (Koskimaa 1997a)

[16] In addition, the figure mapping the cross-continent trip a little resembles the cognitive maps of hypertext fiction.

[17] Eskelinen 1997. See also: http://www.kolumbus.fi/mareske

[18] This usage was started by Landow, who borrowed the term from Roland Barthes.

[19] Cf. Moulthrop 1995; Glacier 1997.

[20] Change the words "in hypertext" for "TIOLI", and it is still as accurate a description: "Rather the act of reading in hypertext is constituted as struggle: a chapter of chances, a chain of detours, a series of revealing failures in commitment out of which come the pleasures of the web, or the text." (Moulthrop 1995, 74)

[21] Rosenberg 1996c.

[22] Rosenberg 1996a.

[23] May's argument would be acceptable if he would stay on his explicit topic: the problem of constructing the fictional reference world from the textual evidence given in Mulligan Stew. His rhetorical discourse, however, is full of normative expressions giving the impression that fictional texts should provide the reader with sufficient materials for this, and furthermore, that is what every reader should do.

[24] Paradoxically, it is just through the emphasis on the heterogeneity of the materials how Mulligan Stew might be made more easily accessed: if the drafts were more draft-like in their appearance, if Lamont's notebook excerpts were in handwriting, the items from Scrapbook in their original appearance - as they very likely were, should someone transfer the book to hypertext format - I am pretty sure there would be no problems for most of the readers because of the heteretopicality (while excessive self-referential metafictionality is still another question).

[25] Cf. Berger & Luckmann 1966; Cohen & Taylor 1978.

[26] Iser's most recent studies in "literary anthropology" naturally shifts the focus towards real audiences, but leaves the reading process behind.

[27] See Ryan 1991 for systematic definitions for narrative, fiction, and literary, and for a thorough classification of their possible combinations.

[28] I have limited myself here mainly to hyperfiction. There are, naturally, a number of other forms of ergodic texts in use, but the problem with those is, they not only push the envelope of narrative fiction, but that of "literature" in general.